I like the following quotation from Bosanquet in Susanne Anger’s 'Mind: an Essay on Human Feeling’, which encapsulates the two forces that have shaped my life: Dance and Pain.

‘In common life your sorrow is a more or less dull pain, and its object – what it is about – remains a thought associated with it. There is no new depth of experience promoted by the connection. But if you have the power to draw out or give imaginative shape to the object and material to your sorrowful experience, then it must undergo a transformation. …. The feeling as finally expressed is a new creation, not the simple pain … that was felt at first.’

nature of neuropathic pain. The music is Mama by

Genesis, which acted as a real inspiration.

I came to theatre as a dancer. My mother, who loved dance and made a formidable ballroom couple with my father, took me to ballet lessons when I was four. I distinctly remember her watching with other mums as I was sometimes praised, but also gently reprimanded for my ‘sticking out’ tummy and failure to perform recognisable cartwheels … all part of ballet’s rich pattern! I was invited to audition for the Royal Ballet School, but, not wanting to leave home at the tender age of eight, I continued with my ‘academic’ studies, much to my father’s relief.

I first went to St Anne’s convent, Weybridge, my mother’s childhood school, and, as an October baby, took a preliminary exam which enabled me to sit the eleven plus a year early. I passed and went on to the local grammar. This was Sir William Perkins’s School, Chertsey, the junior part of it at Pyrcroft, the lovely old house which Oliver Twist is reputed to have burgled.

‘Student life’ at such an institution in the fifties was quite dull, the teachers and teaching methods uninspiring. But I did enjoy languages - French, Latin and Greek - and have vivid memories of the ‘characterful’ teachers involved. In the 3rd year sixth, at that time the Oxford entrance term, I had to translate Shakespeare into Latin, which I relished, although there’s no way I could do it now! I would climb the stairs to my cold bedroom and sit by the one small electric bar heater, a glass of Newcastle Brown at hand ready to tackle the beast …

I remember being rebuked for smothering a laugh with a friend at Coleridge’s line from his poem Kubla Khan, ‘The earth in fast thick pants is breathing’. Together we had naturally interpreted the fast thick pants as vast thick pants … I was reprimanded for being ‘smug’, but wouldn’t any normal teenager find that funny? Unsurprisingly, Coleridge’s poetic line connected with memories of shivering on the pitch when obliged by the unrelenting games mistress to play hockey in below freezing temperatures, wearing only our thin Aertex shirts and baggy navy knickers (mine came down to my knees we were, in our very own vast thick pants, shivering, our breath sparkling on the freezing air …

I was definitely one of that long-gone 1950s ‘socially mobile’ generation, benefiting from the now controversial selective school system. Apparently educational research has shown that, after the war, children of factory foremen like my father, would go on to achieve academic success unparalleled before or since; so I was a merry statistic, one of that privileged band!

Ancestors on my father’s side were Huguenots who escaped from Boulbec, Normandy, after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, which had led to the mass persecution of Protestants in France. These exiles settled in the East End of London, so my father was a true Cockney, born within the sound of Bow bells … actually in Bethnal Green, at that time a large slum area. His father made corsets for ladies’ gowns before becoming a carpenter. His mother was one of the first female members of the Fabian society, founded in 1894 ‘to educate, agitate and organise … for the betterment of society’, so my father was brought up from childhood with an interest in political change. Apparently the family – parents and six children – having moved from Bethnal Green to Kingston for my grandfather’s work, then walked twenty miles from there to a small cottage in Addlestone Moor, which was where I visited them as a child.

My father could easily have passed a scholarship to a grammar school or equivalent, but in the early years of the twentieth century wasn’t given the opportunity. So, having left school at fourteen and working briefly on the land, he eventually became a foreman in the tool room at Vickers Armstrong’s aircraft factory near Weybridge, on the site of what had been the famous Brooklands race track, built by Hugh Lock King in 1907.

at Vickers Armstrong’s

My grandfather, (second from the right), standing with his fellow

workers by the small plane they had constructed. He was the

upholsterer.

He worked there until he became ill in his late fifties with a stomach virus, which was badly diagnosed and treated by a nascent NHS. He suffered much pain from then on, but my mother selflessly took care of him until his death in the 1970s. I remember him sitting silently in our one armchair in the living-room, in the dark, listening to his favourite pieces of classical music on our recently acquired gramophone, of which he was very proud.

Vickers Armstrong’s was the big local employer, during the war making the Wellington bomber, then iconic planes like the Vickers Viscount, Comet and eventually Concorde. At one time or other it employed many of the family, on both sides. My maternal grandfather worked there as an upholsterer,

workmates in a more light-hearted mood!

A more demanding and less savoury holiday job I took as a student was night work with a group of older women, lagging tanks with asbestos. There were no worries about asbestos at that time, but I have to say that I didn’t stick at the job for very long …

The main visual memory I have of my maternal grandmother as she grew older is of her sitting with her feet in the lit kitchen gas oven to keep them warm. The family was always poor, although they did take in lodgers, but proudly not wanting to send her two daughters

Violet, posing for the camera.

Having started ballet classes at four, at the age of seven I danced as a flower in my very first Cabaret. I still have the book of ‘Children’s Stories from the Classics’ that I was given ‘With every good wish and sincere thanks for helping to make our Cabaret a success.’ Signed: D.A.Davidson March 1st 1951.

In 1953, I was one of a group of local kids who played each evening on the nearby building site – wouldn’t happen now! Together we created a review type ‘event’ to celebrate the Coronation, which we watched on my grandparents’ nine inch television. The ‘review’ was to be a special entertainment for our parents, performed on a patch of waste land amid the general dross. I sang a hymn and danced a little dance in my Coronation costume, white and blue with red bows. However this opportunity to be with other children was, sadly, a one-off for me, as the building site was soon full of houses with people shut up inside them. Our playground had disappeared.

Coronation costume, white and blue

with red bows.

I was an only child. My parents decided to wait until the war was approaching its end before having children, and when my mother had two miscarriages decided that I should have ‘All the advantages and benefits that they hadn’t been able to enjoy’ as she later told me, and didn’t try for more. So no pressure then!

With my ballet classes, I had elocution and piano lessons from the age of eight. We didn’t own a car or a television, but I was fortunate that my father would save his pennies to take my mother and me to see ballet and opera at Covent Garden; we would sit in the best seats in the stalls to enjoy Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle, Madam Butterfly and Tosca etc. Although of course I wasn’t aware of it at the time, witnessing such beauty in an environment like the Royal Opera House must have played an important part in my own artistic development.

When I gained a Distinction for Grade 8 piano in my teens there was some discussion of me going to music school, but my cold, judgemental teacher had not inspired me to have any enthusiasm for the piano and I gained no real enjoyment from playing. Practising was always a chore, but necessary, as I was entered for many music festivals; I still have the medals won. My mother would always accompany me, sitting to watch me play, which I hope was not too tedious for her!

I loved Art, but when it came to making decisions for ‘O’ level was obliged by the headmistress to take Physics, of which I remember nothing except my dislike of the subject. I think that, as a Lady Margaret Hall graduate herself, she already had the idea that I might go to Oxford and was convinced, rightly or wrongly, that I needed a science subject apart from mathematics to be considered.

I didn’t go to the local Primary or Secondary Modern, and as a grammar school pupil lived far away from other school friends, so, without transport, was unable to see them after school hours. My parents were both at work when I was eight, which meant that I spent lonely days at home in the school holidays. I had to develop ways of occupying the hours; apart from doing simple housework, I would read, draw, paint and then practise the piano for an hour every day. There were also times when I would do nothing more than rock back and forth in an armchair, sometimes gently sobbing. I have since been told that this is a classic behaviour for only children experiencing loneliness. Viewing things more positively, I’m sure my youthful creative activity must have contributed towards what was to become an artistic future.

I sometimes feel guilty that I didn’t show enough love or gratitude for everything my parents had given me; I took things too much for granted. At school, particularly after passing the eleven plus, my life was dominated by the demands of academia and the artistic activities my parents had favoured for me. These allowed me to be alone or occasionally with contacts of my own age, and sadly I now feel that my relationship with my parents was relatively distant.

However, eventually becoming more confident and out-going in the sixth form, I began to form friendships with boys at the local boarding school. I understood very little about sex – I think chiefly because I had to take a piano lesson during the one ‘Physical Relationships’ class given by the Games mistress …

At the age of seventeen I developed a close friendship with a local boy, Ian, a pupil at the boarding school, who played jazz piano, smoked like a chimney, was very good-looking and loved literature. We used to go for a drink together at the local pub and then night-time walks in the nearby countryside. He would break bounds from school and take the train with me to London to see the latest new-wave French films, until he was caught one night climbing over the wall back into school and duly expelled. Fortunately, however, one teacher thought highly of his academic ability and gave him private tuition, which led to a Cambridge scholarship.

Although we were ‘in love’ for some time, we eventually broke up, but I still think about him with affection. He was the first to make love to me, actually in a small and rather picturesque graveyard, which was the end point of our nightly walks …

A big adventure just before I came to Oxford was hitch-hiking to Greece with a boyfriend from the local boys’ grammar school, who went on to become a Lecturer in Maths at Oriel College. This was in the summer of 1963, and cost us £25 each for the month. I had met Peter through our mutual love of traditional jazz – we danced together at events like the Ally Pally (Alexandra Palace) stomp and at Eel Pie Island, a great meeting place for followers of Chris Barber, Acker Bilk, Ken Colyer etc.

through Europe

We hitched from Tours in central France, where I was taking a language course, down through Italy, across by boat to Athens from the port of Brindisi, up through Greece, stopping off at the island of Skiathos, (where we stayed for a few days in a cave), then home via what was then Yugoslavia. We travelled very simply, carrying just the minimum in our backpacks, (for me, a sheet sleeping bag, two dresses, basic underwear and soap, toothbrush etc). We often slept by the roadside if no cheap or free resting place was offered or presented itself. I was approached one night when sleeping in the industrial areas inland from Venice … he said asked ‘Vuoi fare l’amore?’, but when I answered ‘no’ just walked away. I wonder if that would happen now?

I have too many memories of the adventure to include them here, but I can’t forget being more or less alone on the Acropolis, or just the two of us visiting Delphi in the early morning – no-one else there – or sleeping on the Ile de Paris with a load of other hippies. Then Greek hospitality – we were invited into so many homes where we were wined and dined on our travels. The autostrade in Italy were in the process of being constructed, so we had to ride in lorries and old cars on many dirt tracks; Southern Italy seemed full of wild women in flowing black robes. We travelled in a gondola at night in Venice, the canals calm, silent and totally free of other traffic – magic!

Dance had continued to play a big part in my life during my school years, but having rejected it as a possible career, I took Oxbridge entrance exams and in 1963 went up to Lady Margaret Hall to read Modern Languages: French and Latin. Curious that Latin was part of a Modern Languages degree in the early 1960s but I’m very glad it was! As a student, my interest in dance soon led me to become President of the O.U. Ballet Club and I devised and directed several dance performances. The first of these, imaginatively titled ‘Mood and Movement’, took place in the airy vastness of Talbot Hall, LMH. It included pieces ranging from a danced version of Peggy Lee’s Fever to a movement interpretation of poems by Gerard Manly Hopkins. Two students from the Sigurd Leder School of Dance, which I had briefly attended before coming to Oxford, took part to raise the tone of the evening ... (Sigurd Leder had been a pupil of Rudolf Laban, whose teaching method I was to follow when I myself became a teacher of dance.) Music was played on a gramophone, a student friend acting as ‘sound engineer’, carefully tending the needle ... The evening was complimented by the then Isis reviewer for being ‘superb’ and ‘fascinating’, in contrast with an Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS) musical in the Newman Rooms, which was, in his opinion, ‘just fourth-form’.

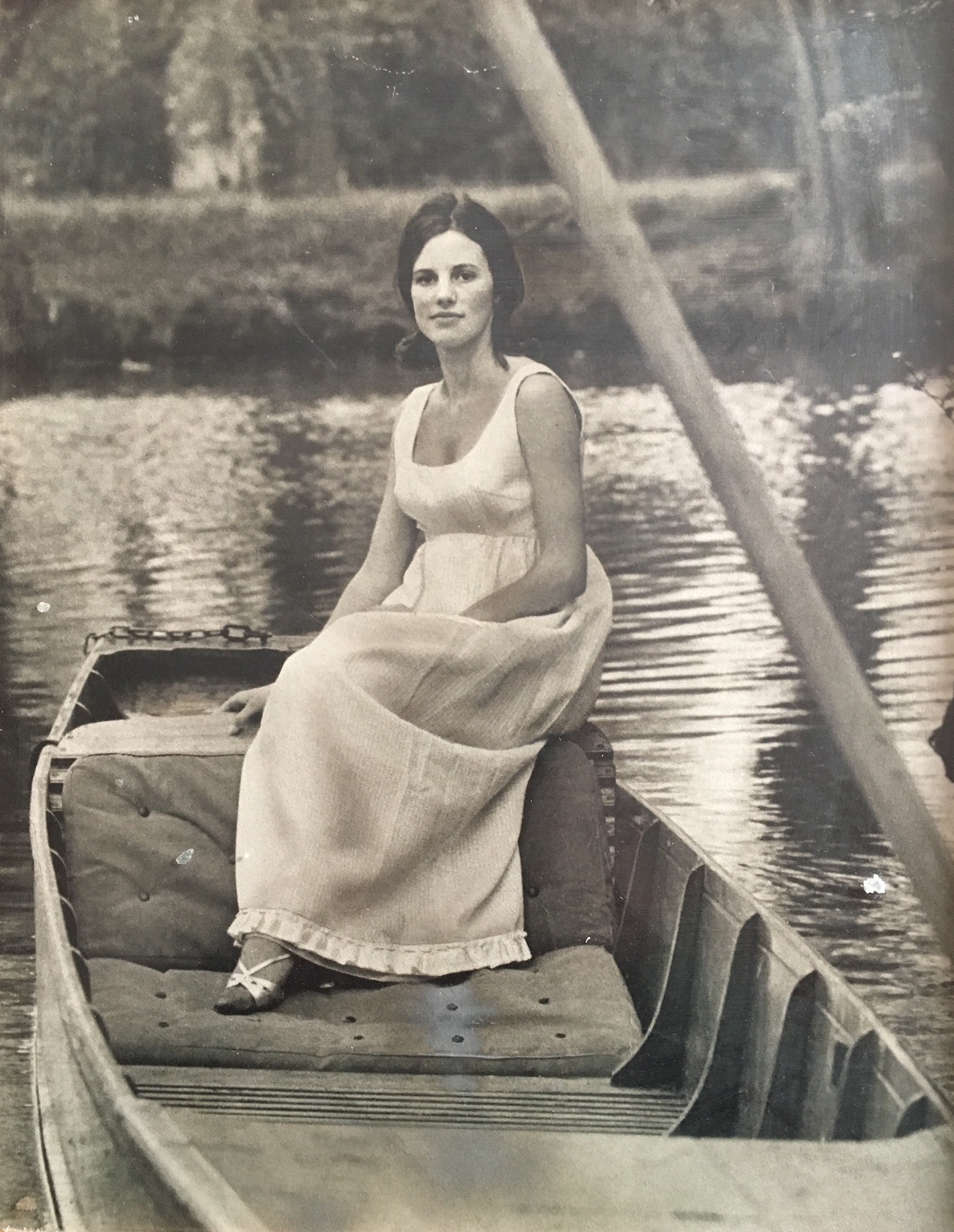

A photo taken for the Daily Telegraph of me on a

punt at LMH. I was wearing a homemade Empire line

ball dress costing £3.00. The article was called

‘Grandeur on a grant.

We were very lucky to have the opportunity to study mime with international mime artiste, Lindsay Kemp, a charismatic personality and teacher, noted for his no-nonsense ‘hands on bra-straps’, ‘hands on stocking-tops’ way of persuading the class to adopt basic hand/arm positions. With his blind dancer friend, Jack, he had been one of a very small audience at our performance of Masquerade at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

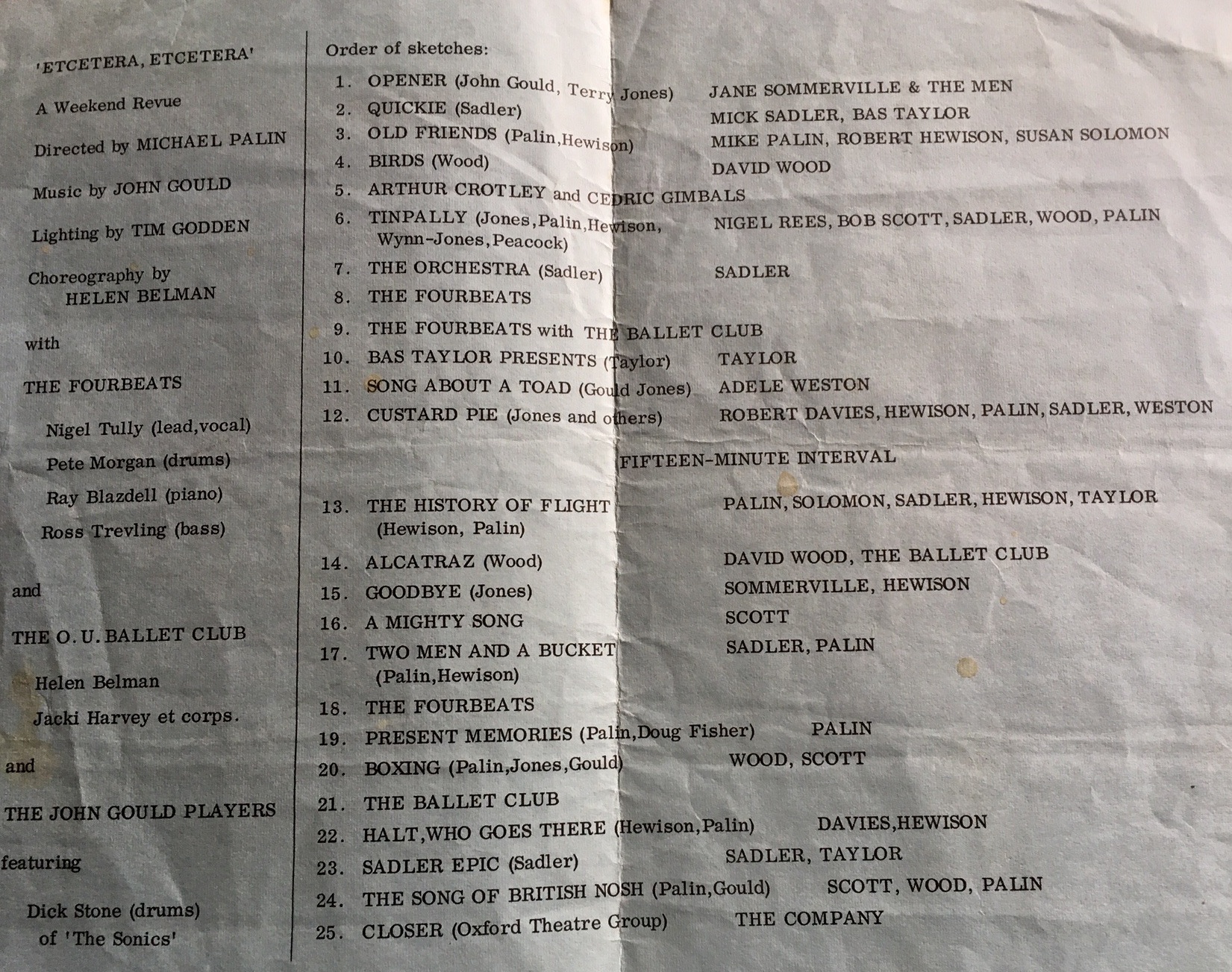

Masquerade was a devised Commedia dell’Arte piece which a group of us from the Ballet Club had created during the summer term of 1965. We used recorded music, mostly from the popular ‘60s film, Jules et Jim, and involved a student friend, an expert drum and tambour player, for special scenes. This formed part of the Oxford contribution to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, at that time small and relatively navigable. The Oxford programme included review with Mike Palin and Terry Jones and the first public performance of Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. We performed at Cranston Street Hall and slept on the floor in the Masonic Lodge, at the top of the Royal Mile. Apparently the students whose job it was to cook for us all left the Festival suffering from malnutrition …

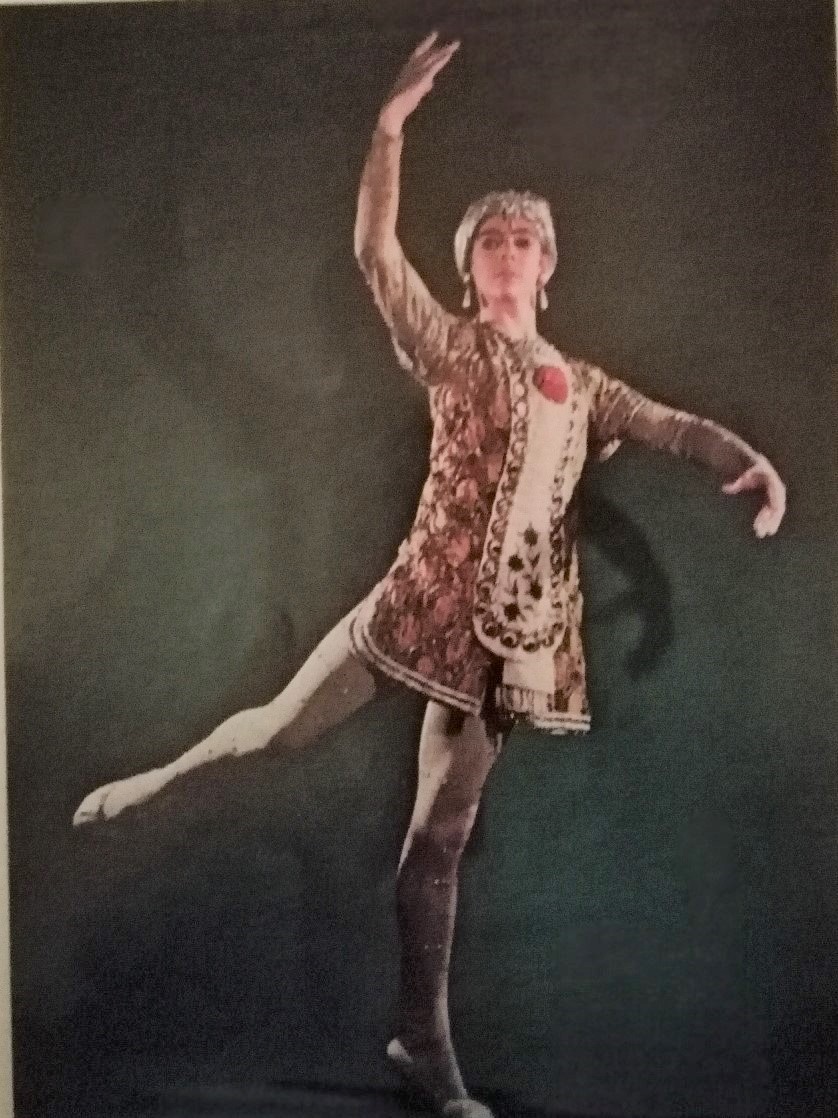

‘Masquerade’at the 1966 Edinburgh Festival

Having seen Masquerade, Lindsay commented afterwards, ‘Dears, I had tears just runnin’ down my cheeks!’, and then came regularly to teach us, for free - as one did in those days - at LMH. I remember Oxford Playhouse director, Frank Hauser, engaging him to perform in Ben Jonson’s Volpone; he was Nano, the dwarf, acting the part convincingly on his knees throughout the entire play!

As President of the Ballet Club I was also able to invite dancers from the recently founded London Contemporary Dance Theatre (LCDT) to demonstrate for us, and worked with other teachers instrumental in bringing modern dance forms from Europe and the States. Whereas much had been happening in the USA since the 1930s with choreographers and dancers like Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham, it was really only in the ‘60s that things took off in the U.K. This was when Robert Cohan, one of Martha Graham’s original dancers, and Robin Howard set up LCDT at The Place in London, since its foundation one of the most frequented venues in the U.K. for new dance forms.

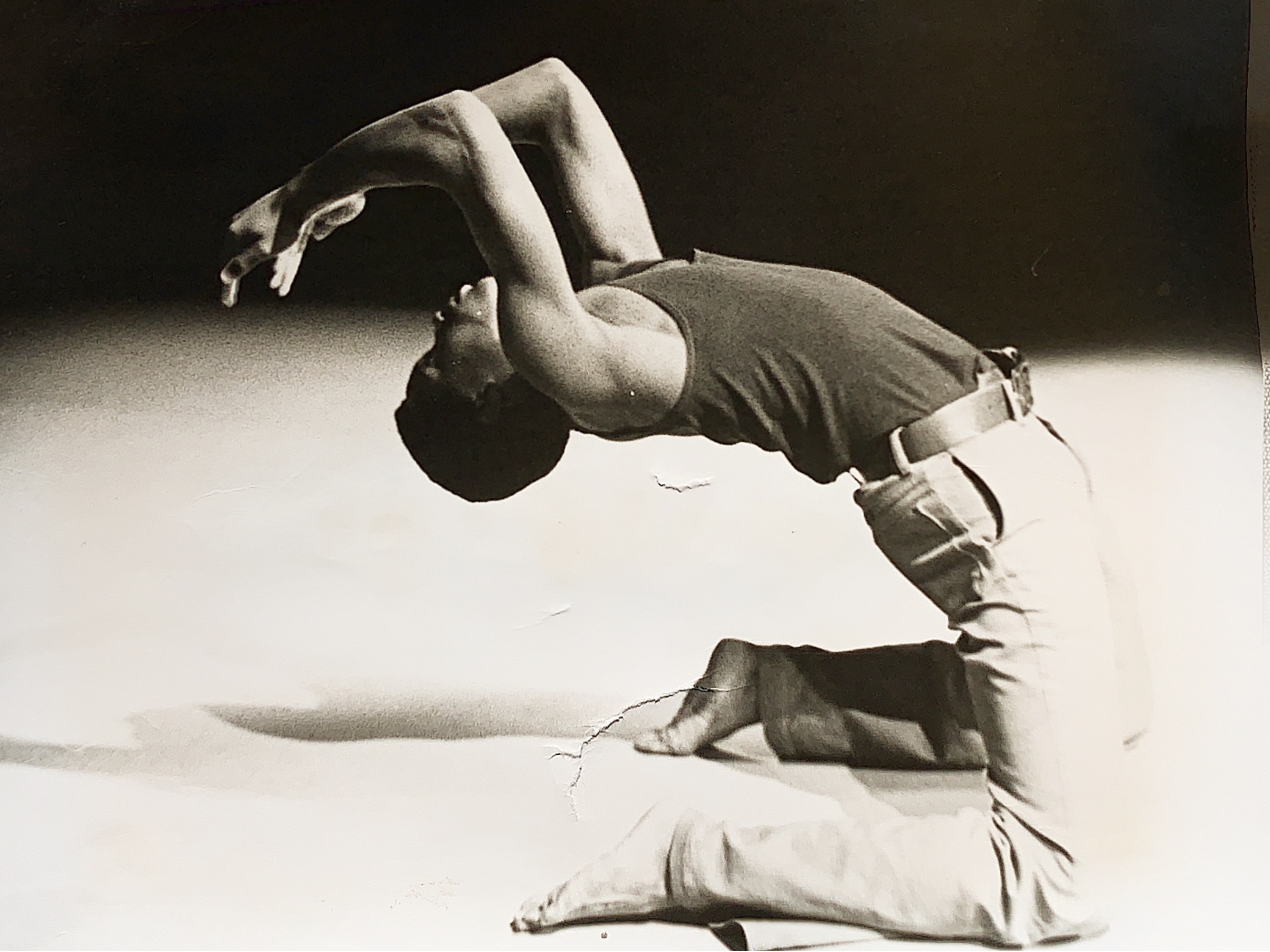

.jpeg)

So after a childhood spent ‘straightening my back’ and ‘turning out my toes’ in satin ballet shoes, I was enthused by these fresh techniques. I learned to be ‘floor based’, to flex my now bare toes – quite strange and painful at first – to ‘contract’, ‘isolate’ and ‘release’ my centre to order. This was my first real contact with what was to become the Contemporary Dance movement in the U.K. and although, at one level I took it all for granted, I found it very exciting. It was to become the basis for one of the ways in which I was to perform, choreograph and teach from that time on.

Members of the Ballet Club danced in termly reviews at the Playhouse with Michael Palin, Terry Jones et al. I still remember watching from the wings and being moved by a Palin sketch, which was not just comic but deeply poignant. In my third year I was asked to choreograph the Richard Burton/Elizabeth Taylor Dr Faustus, surely the most prestigious theatre production of our generation. (See Faustus 1966 production.) Although far from being a great performance, Dr Faustus was a very enjoyable experience; it presented new opportunities for choreography which I relished, particularly working for the first time with a live composer.

Terry Jones. The O.U. Ballet Club was conscripted to perform

a dance

My time at Oxford was certainly coloured by the music of the Beatles, who brought the sixties to life for us all. A group of excited students would meet every Sunday in a small room in LMH to listen to Top of the Pops, when their latest hit would be revealed … fantastic! It is said that one of the reasons the Beatles’ reputation stands so far above their contemporaries is that their recording career lasted just seven years; as a carefree student I was very lucky to be at an age to revel in the optimism of what I think were their best years, 1963-1966, and in the legend of inspirational music, of love, joy and freedom that they created.

In 1968 I was the first to study for an M.A. in Dance, Drama and Theatre Arts at Birmingham University, at £75 for a year of virtually private tuition. While there I studied the ‘Laban method’, (mentioned previously in connection with Sigurd Leder) which I have found a life-enhancing and constantly inspiring approach to movement ever since. Rudolf Laban was a central European dancer, choreographer and teacher who developed a system of movement education which spread through Europe in the 1930s. The Laban Art of Movement Studio was founded in Weybridge, Surrey, which is where Laban died in the late 1950s. Without being aware of it, I had actually attended classes in the ‘Laban method’ there before coming to Oxford.

Following Laban’s analysis, the student will develop an understanding, at all levels – physical, mental and emotional - of the sixteen basic movement themes which constitute our daily lives. It’s not just ‘another technique’. Working through improvisation, alone, with a partner or in a group, the dancer will experience the vocabulary of body awareness, awareness of weight, time, space, flow and relationship, all of which we use spontaneously to communicate, to work, when we are alone, indeed at every moment in our lives. These movement themes, once explored and understood, can then be used expressively, ultimately in the creation of a dance. As Laban said, ‘Dance is no static picture, no allegory, but vibrant life itself … The new dance technique endeavours to integrate intellectual knowledge with creative ability, an aim which is of paramount importance in any form of education.’

As part of the M.A. course at Birmingham I also discovered old and new styles of acting and directors: Stanislavsky, Meyerhold, Grotowski, Artaud and Brecht, for example, all of whom I found ultimately stimulating. I wrote my M.A. thesis on ‘The Contribution of Designers and Composers to the Diaghilev ballet company’ which involved a period of fascinating research for me. During the summer of 1968 I worked in Covent Garden as a sub-editor of The Dancing Times magazine, and while there had the good fortune to attend exhibitions at Sotheby’s of Diaghilev Ballet Material which, quite by chance, were showing at that time. Costumes and sets by Bakst, Benois, Derain, Picasso etc. – they were all there!

Sotheby’s exhibition

I did not know then how all these things – my growing understanding of the importance of the physical, my love of language, drama and dance - would become part of my life work in years to come.

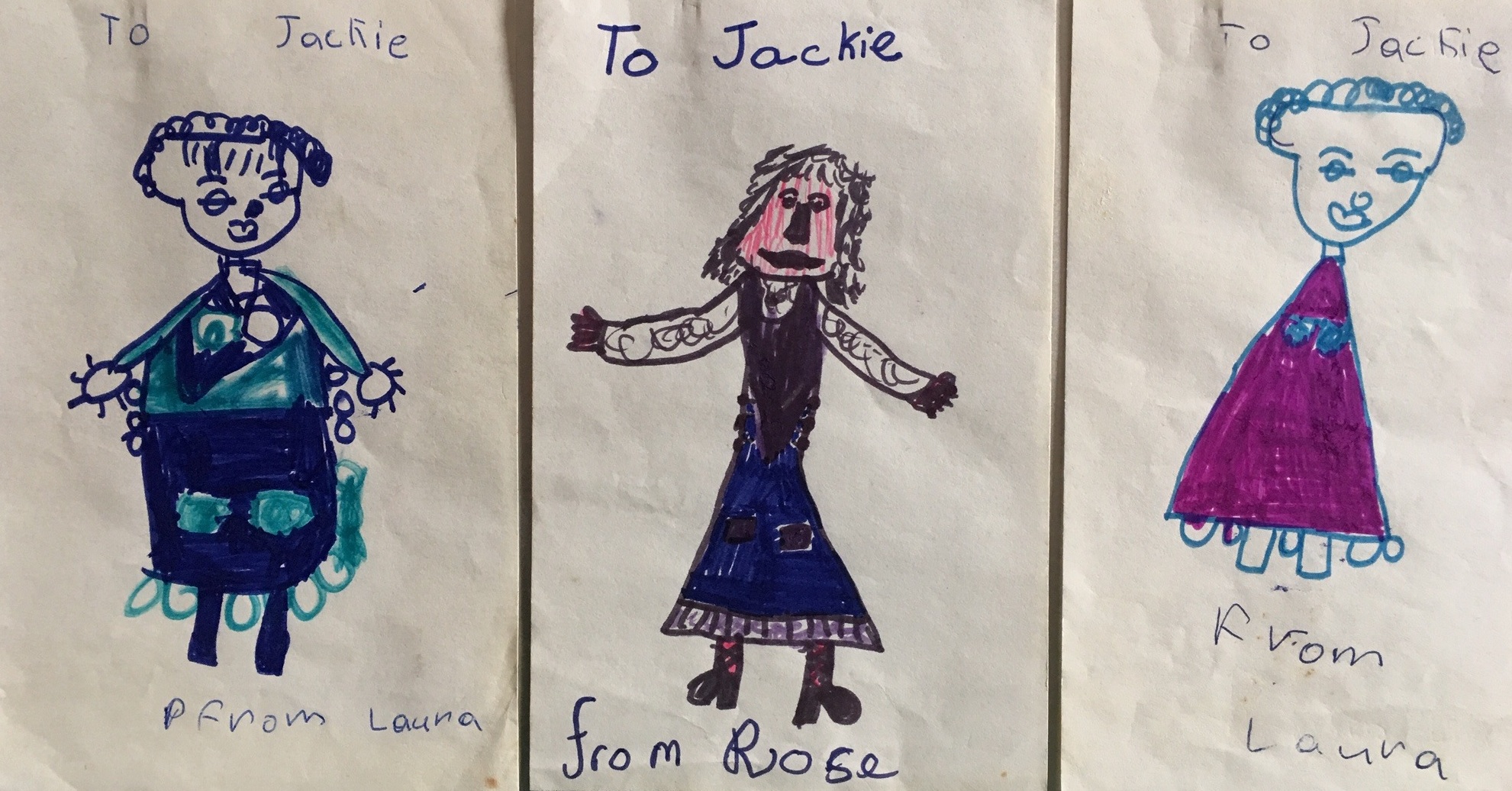

At the suggestion of my tutor, I auditioned and then performed with a small Dance in Education Company, the British Dance Drama Theatre (BDDT), in schools and colleges throughout the U.K. I particularly remember the poverty of the Welsh valleys and the primary schools in the north of England, where children would crayon pictures of me as a Princess and the Dancing Broom in Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. We earned the magnificent sum of £19 per week, stayed in a variety of cheap digs and were all on very close terms. There was one memorable B&B in Liverpool which was so cold that we had to gather round the light bulb in the bathroom to keep warm! Intimate friendships were formed on that tour, including one between myself and my future husband for seven years, Michael.

Back in Oxford, Gerard Gould, Head of English at Lord Williams’s boys’ grammar school, Thame, had seen me dance in our performance of Masquerade at the Playhouse in 1965. He knew of my interest in theatre and the Performing Arts, and that I had completed a Diploma of Education (PGCE) while at Oxford. When my BDDT contract ended in 1970, he suggested that I apply for a post teaching Modern Languages and Drama at the school, which had a very strong reputation for its education in the Arts and education via the Arts. It was about to become a mixed Comprehensive, so beginning to employ female teachers. I got the job and was to be one of two young women on the staff.

I had just spent a year performing in schools and colleges, so it seemed a natural move actually to start teaching the subjects for which I had a special affection. I knew that Oxford was a city where my interest in the arts could continue to flourish via University and Community contacts, so a good place to be.

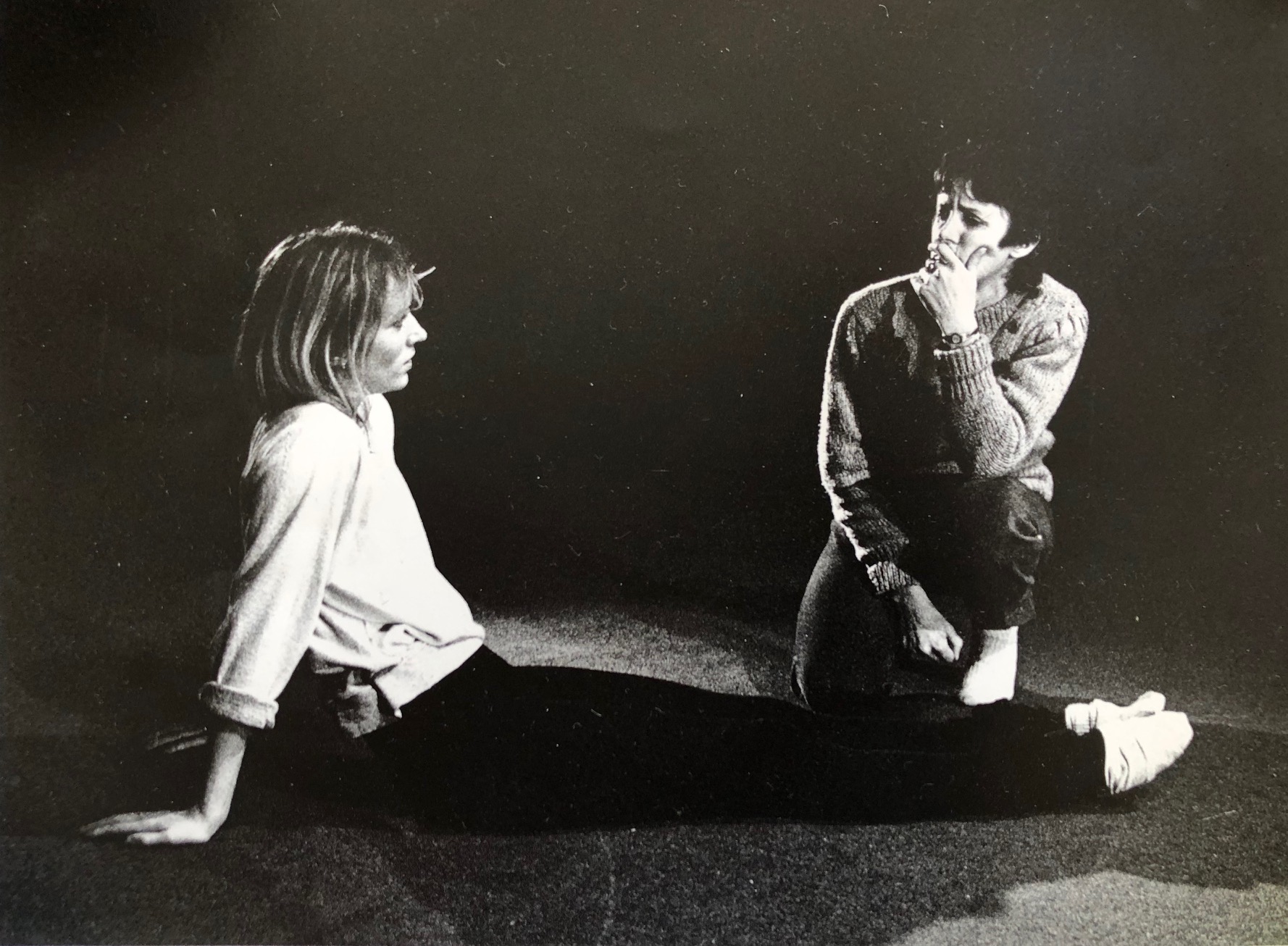

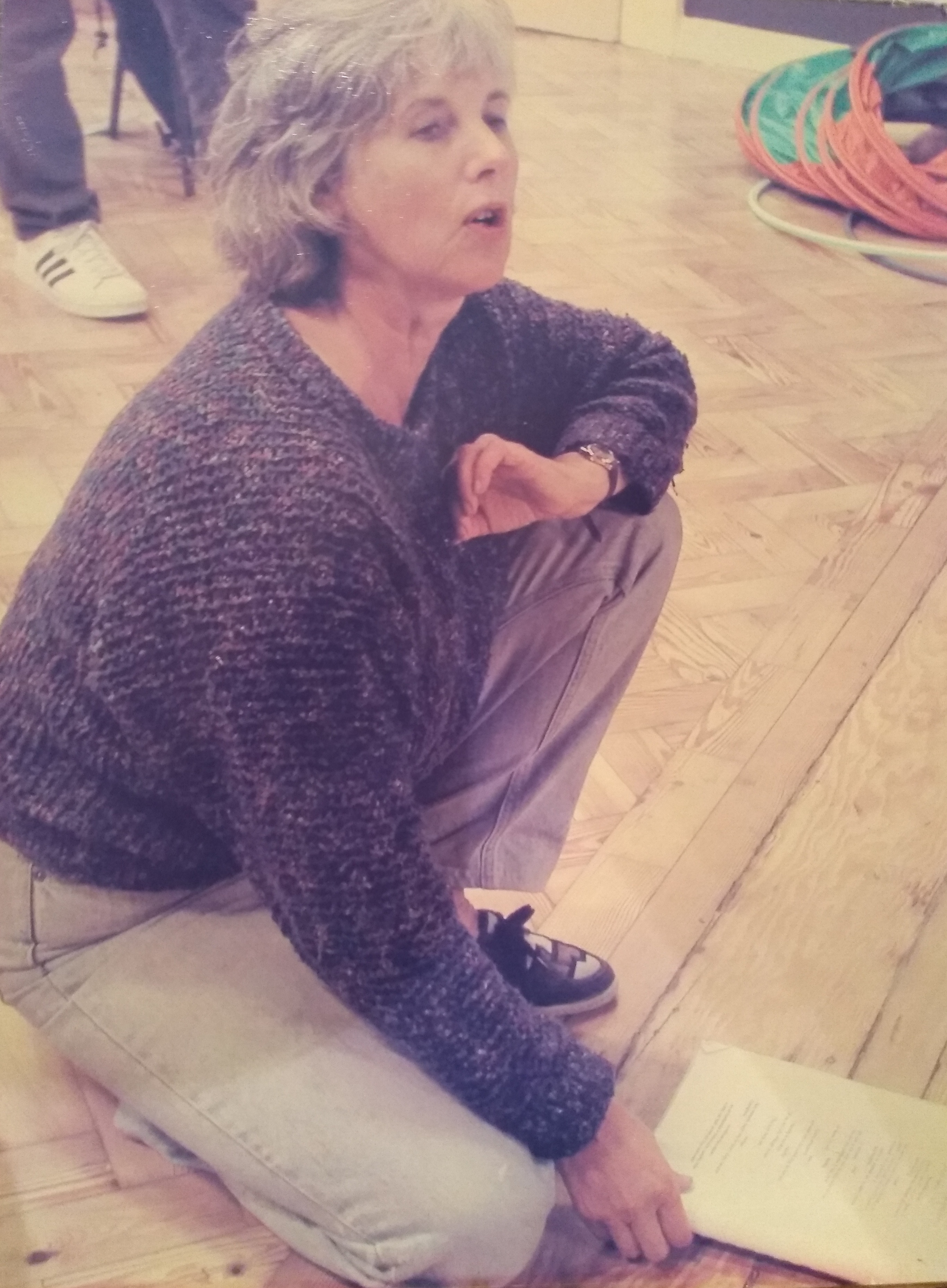

Gerard very soon asked me to teach Dance-Drama with the sixth form General Studies group, then just boys. This was a cutting edge move as it was rare for boys to study Dance in state education at the time. There was a project in view: to devise a physical theatre piece for a competition based on a production of Peer Gynt at the Oxford Playhouse. We won the competition with our highly abstract movement interpretation; Solveig, for example, was portrayed by three boys moving in harmony throughout, to reflect her continuing loyalty to Peer Gynt, while other boys were dancing with simple, overtly meaningless objects to show the vanity of human greed and obsession.

for a dance performance

The group went on, by request, to perform at Eton, a novel experience for us all … We were well reviewed in the 1970 Eton College Chronicle, which noted the reactions of the boys watching, most of whom would have had little or no experience of dance. ‘The group demonstrated that expressive movement was highly interesting and deceptively easy – it was difficult to believe that they had only been working together for a few months … Many thanks to the students and their teacher for an entertaining and stimulating evening.’

Actually I should admit that the Thame boys’ main memory of the evening was the fact that they had shared cannabis with their sixth-form hosts while their teachers and I were at dinner ... But I’m sure they also enjoyed the pleasure they had given their Eton audience, a learning experience in itself.

When Lord Williams’s became comprehensive I was appointed Head of Dance, and taught a CSE course established for girls coming from the local Secondary Modern to join us. Sixth form General Studies classes were still open to all and I was surprised and delighted when boys actually asked if they could join in. I taught via the Laban Method, at that time termed ‘Modern Educational Dance’. This was the way of teaching to which I became ever more attached as my career developed and I came to understand its relevance to the educational process as a whole.

I find these words of Peter Abbs in his book Reclamations particularly relevant to my own philosophy of dance in education: ‘Perhaps wholeness of being is the ethical goal which all aesthetic activity, consciously or unconsciously, moves towards …Wholeness of being … will have to include, in a tense balance, all the elements of the human psyche: thought, feelings, sensation, intuition, imagination and instinct. I would contend that the arts, because they actively engage, in one way or another, all these elements, are best equipped to contribute to the development of such an ideal. The arts do, sometimes quite dangerously, enlist the magnificent monsters of the passions, but they also enlist the constructive, cognitive and form seeking energies of the mind.’

And perhaps a quotation from Karl Marx is apt here. ‘The development of human power as its own end is the true realm of freedom. It is of supreme importance to educate the growth of the senses …. The goal is to give birth, not to possess or utilise.’

This last might seem to have a much weaker connection with my primary thesis, but it is still ultimately relevant. Before his recent death, Clive James quoted T.E. Lawrence, who said, ‘Happiness is a by-product of absorption.’ Surely this relates to Abbs’s thoughts on the ‘wholeness of being’ to be experienced via artistic activity, dance being perhaps the most absorbing, of mind, body and spirit. So dance has a benign link with happiness ….

Inspired by Abbs’s book, I went on to collaborate with local schools in the making of a film, Dance in Education, to show how movement could be used to teach Biology, English, Mathematics and Art. Students involved took the part of cells in the process of cell division or of brush strokes in the paintings of Van Gogh, attaining a mind-body experience of activities in the Arts and Sciences.

Having had sessions at University with dancer/choreographer, Gregg Mayer, members of LCDT, the Sigurd Leder School (Leder had been one of Laban’s students - before coming to Oxford I had attended his classes in London) and others, I also taught Contemporary Dance, my teaching in this context chiefly based on the ‘contraction/release’/floor based methods of Martha Graham.

I particularly relished the music of Pink Floyd as inspirational accompaniment for a whole range of ideas - I count myself very lucky to have been creating dance when they were on the scene! I was inspired by their music to choreograph a series of dances about ‘The Body’: Muscles, Joints, Vocal Chords, Equilibrium, Vision etc., which formed part of a ‘superb’ programme performed to an ‘enthralled’ audience at the Round House theatre in 1975. I also used Pink Floyd for dances with the sixth form group to enact themes such as the Agamemnon and the Tarot Cards - not run of the mill stuff, you might say, but definitely a learning experience for the students and much enjoyed by audiences.

who gained a scholarship to LCDT school.

Annual Dance-Drama Evenings often involved more than one hundred students of different ages who would tell stories, portray feelings and relationships or express musical ideas. In the footsteps of Laban I would complete performances with what he would have called a ‘Movement Choir’, the whole cast dancing together to the music of Verdi or Beethoven. Here his philosophical aim was to create ’festive occasions … deepening the sense of mutuality and personal identity of each individual.’ Remembering now the response of dancers and audience I think we achieved what he wanted.

Sixth form students were asked to perform at schools, colleges and venues including the Young Vic, Cockpit and, as already mentioned, the Round House. In 1975 this was a large open space where the audience sat literally ‘in the round’, their attention focused on a relatively small central stage, which suited us absolutely. We received many positive comments eg from teachers at a school in Waltham Forest: ‘We were all full of awe and admiration for your achievements and it has made the kids want to get involved. … it was obvious by the simple costumes, props etc., that most of the kids had no special talent, that the chief reason behind their achievement was involvement and enjoyment and the way they had been taught.

performance at the Roundhouse

‘It was exciting to see young people dancing with such skill, total absorption and the ability to project and communicate. The presentation and production equalled any professional company and we felt privileged to watch it.’ Diana Gamble, Head of Dance, Bedford College of Physical Education.

What higher praise could one hope for? My one regret is that we didn’t acknowledge the audience’s appreciation and vibrant applause by taking a bow … I wasn’t into ‘taking bows’ at that time so we hadn’t prepared for one. I only learned later that the members of the audience like and need recognition as much as the performers …

In the ‘70s I began to teach the Laban method abroad, principally in Scandinavia, but also in Holland and France. I relished teaching in many different locations in Sweden, mostly in Stockholm for an organisation called Studieframjandet, but also for University drama students in Gotenberg, other towns and cities in central Sweden, and Lulea, beyond the Arctic Circle. The country became like a second home for me … arriving on the plane I would find myself singing ‘I’m coming home …’ from Pink Floyd’s The Wall. I worked with people from all walks of life: actors, singers and dancers, school students and hospital staff, since in Sweden movement was given a high priority for its healing qualities. Then I directed public performances with young people in Stockholm, which was an adventure in itself!

I always very much enjoyed Swedish thoughts and attitudes, their relaxed, cooperative forms of government and priority given to equality in all spheres of life. I liked the climate, even the cold in winter, which was dry and bright rather than damp and grey. I did form a close relationship with a Swedish singer who attended my classes, and the idea developed that I should take a sabbatical year from school to spend teaching in Stockholm while living with him.

However, 14th March 1978 came ‘the event of my life, good or bad’, as I say in the TV documentary which was made seven years later to show how dance helped me cope with pain. On that day I was involved in a road traffic accident: an articulated lorry skidded on a patch of oil, jack knifed and came on top of my car, a Mini. I was taken from the wreckage to Stoke Mandeville hospital, where I was unconscious for three weeks, initially totally paralysed. I knew no one and nothing. I was virtually blind for some months, and even now, forty years after the accident, am much affected by double vision, which is exhausting and difficult to cope with. For example, it is very difficult for me to read after midday as my eyes and face are in so much pain. The saying that ‘the eyes are the mirror of the soul’ comes often to mind.

At the time of the accident in 1978 there was no Post Traumatic Stress counselling or whatever and I had just to ‘strip right off, dust myself down and start all over again’. So, although still partly paralysed and inevitably quite vulnerable, I made a rapid superficial recovery and was back at Lord Williams’s teaching dance and French within six months.

Two years later, when my dance work was expanding, particularly in Scandinavia, I decided to leave school to teach physical theatre and dance as a freelance. But it was then that I began to suffer what was at that time termed ‘thalamic’, now ‘neuropathic pain’, apparently caused by nerve pressure or nerve damage occurring after trauma or surgery. (See Appendix.)

This started as a strange tingling sensation in my face, but soon became, and remains to this day, an all-consuming burning pain invading my face, head, eyes and right upper arm. In the ‘80s it had already developed its own timetable: mornings were relatively pain free, but it was present in the afternoons and would become more dominant into the evenings, although strangely I had more energy to cope later in the day. And this suited my timetable as a future director of Community theatre: I would study the text/have ideas in the morning, swim and meditate in the afternoon to be ready for rehearsal in the evening.

It’s a pain that cannot be seen, so, understandably, there has been little or no sympathy to be had at any stage. As it says in a pamphlet produced The British Pain Society, ‘The hardest pain to bear is one that is invisible. As it cannot be seen it is hard to explain to someone exactly what it feels like. This makes it hard for others to understand just how much it can affect everyday life.’

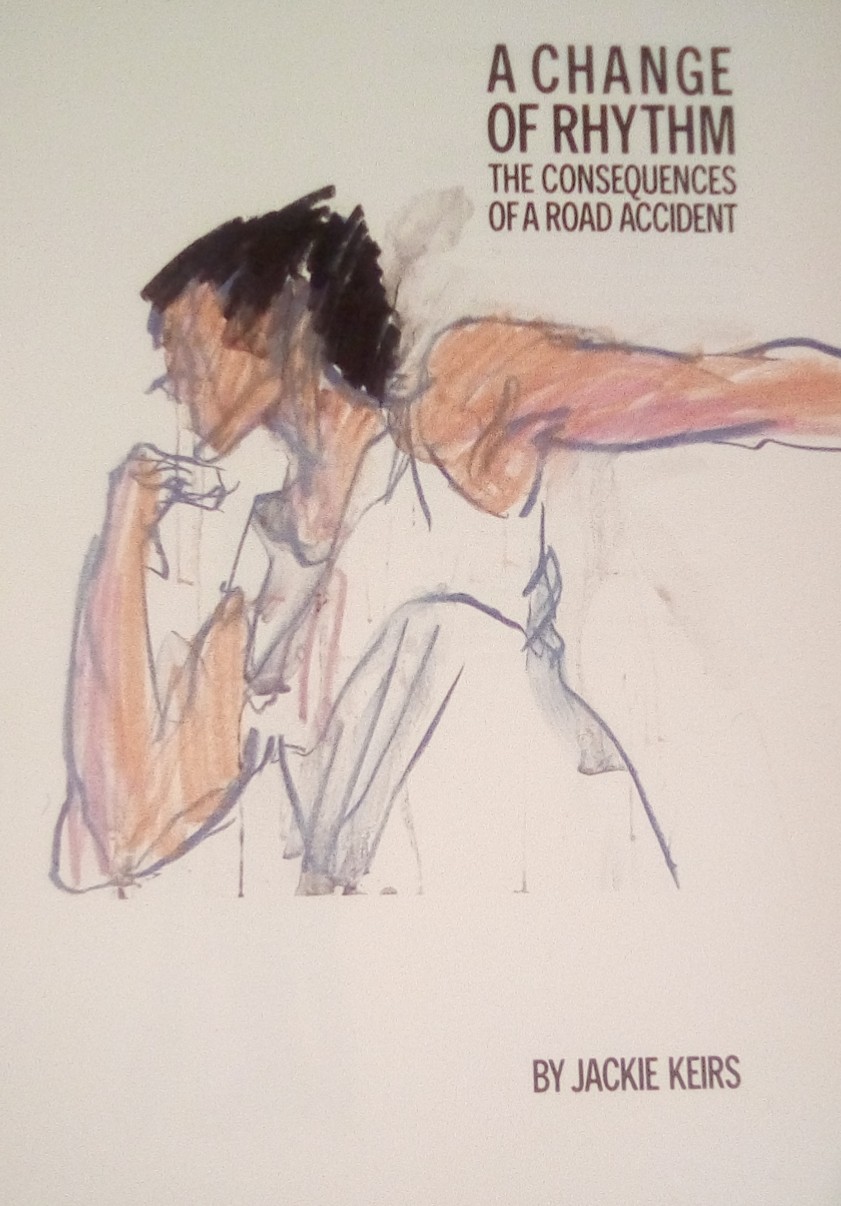

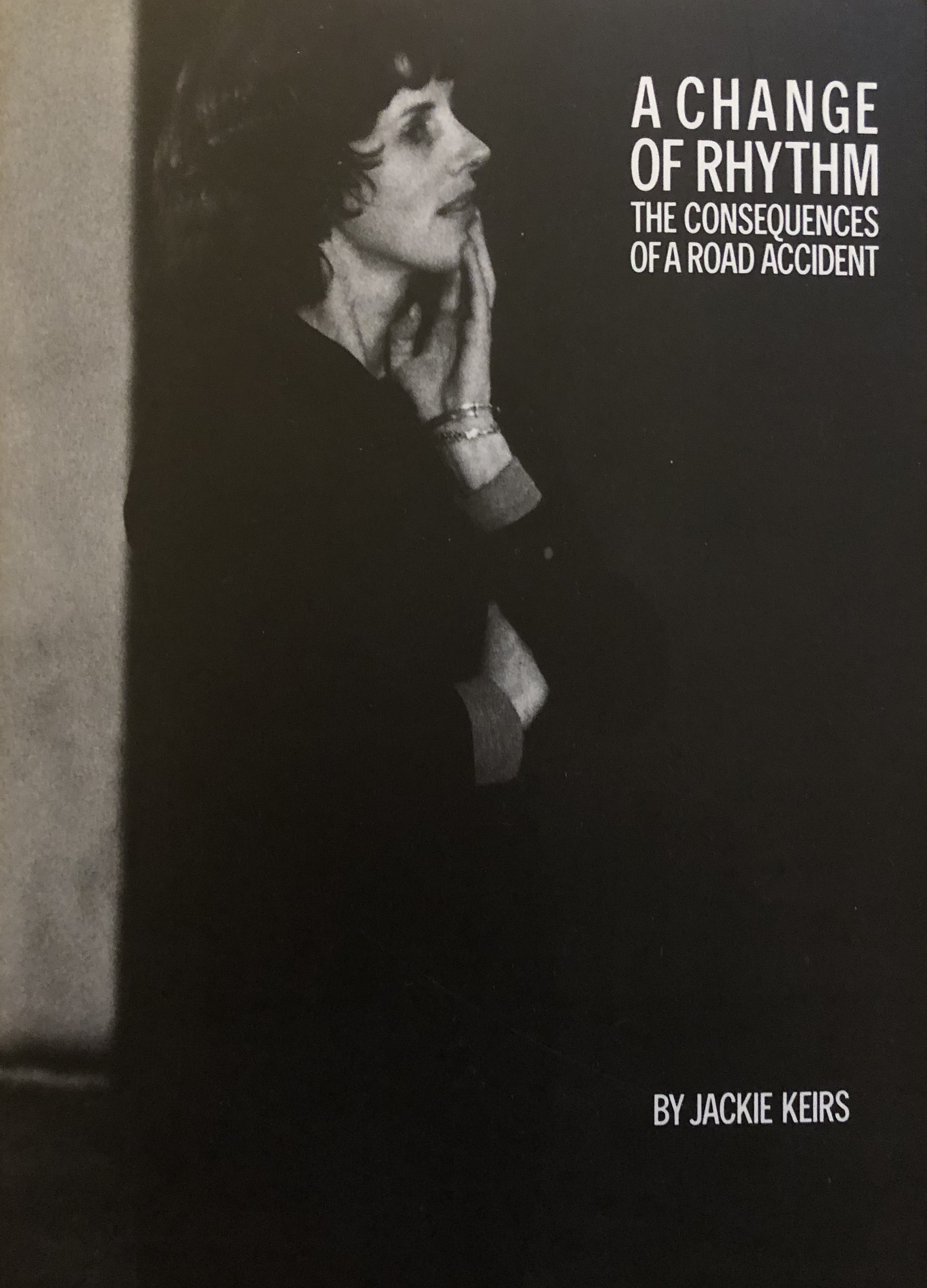

In 1984 I wrote a book, A Change of Rhythm, about the immediate consequences of the accident, and a year later BBC TV made the documentary about me, Living for the Moment, (which would now, I’m sure, be correctly called Living in the Moment!) The film showed how dance, both performing and teaching, somehow enabled me to cope with the rhythms of chronic pain – anticipating, enduring and trying to manage it with meditation, rest, and dance whenever possible.

Illustrations by students at the Ruskin.

I won’t write a full CV, but I did, I think, manage to accomplish some good things during that time. I taught dance and choreographed many productions at local theatre venues, at state and independent schools, as described in previous chapters. At schools, Cabaret, Oh What a Lovely War and The Boyfriend were generally the favourites … I lectured in dance and music at Worcester College of Education, which taught me a lot about music(!); I worked with students of the International Baccalaureat at St. Clare’s College, Oxford, teaching and lecturing on Dance as an artistic medium; I directed an Oxford Operatic production of Bernstein’s Candide at the Playhouse (I chose the opera because I have always relished Voltaire’s philosophical summation of the story: ‘Il faut cultiver notre jardin’/’We must cultivate our garden’ – how true!) I taught Contemporary Dance and Improvisation for Oxford University students and choreographed student productions in college gardens and at the Playhouse: Hamlet, Equus and Royal Hunt of the Sun among them. Actor, Sam West, 1987 President of the Experimental Theatre Club, made a positive comment on my workshops, thanking me for ‘a fascinating series of classes which taught us all a great deal about our bodies and how to use them.’

In fact I did enjoy some real respite in 1991/2 when, having tried every treatment available, orthodox or alternative, I literally stumbled across shiatsu. At that time I was virtually ‘out of it’, but an apparently very simple shiatsu treatment brought me back to life … I was as if released from an enormous weight and could live, for a year or so at least, with totally re-energised physical, emotional and intellectual faculties. As an ordinary member of the human race … Fantastic!

the Oxford Operatic Society

Shiatsu was such a positive experience for me that I qualified as a shiatsu practitioner 2006/7 to be able to give shiatsu to friends and relatives. For me this therapy is a form of healing dance, involving mobility, touch, movement dynamic and relationship; thinking positively it could be seen as a realisation of my life experience.

As described in the previous chapters, I also went on to direct my own company, Oxford Dance Theatre, producing plays and musical theatre from 1987-2007.

Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui at Headington Theatre in 2007 was a difficult play and was to be my last. This was followed by a six month period of depression. During all previous years since the accident I had known I must survive pain in order to reach the end goal, the performance; each year I had given myself something to aim for, involving the talent, skills and commitment of many people to whom I was responsible. Finally, however, it had all become too much. I found myself unable to direct Anouilh’s Antigone, a contrastingly small production at the Burton Taylor theatre which would have blended my love of French and drama. I had been looking forward to it, but in my depressed and weakened state had to cancel.

During the year, however, I gradually emerged from the depression, grew stronger and was invited in 2008 to direct another production of The Soldier’s Tale (see relevant chapter), which was a fitting end to my career. ‘What goes around, comes around’ as they say.

The Soldier’s Tale in Talbot Hall,

LMH, Spring 2008.

Since 2011 I have kept in touch with theatre and theatre friends by organising yearly Cabaret evenings at the Simpkins Lee, LMH. I was first inspired, as usual, by the nature of the space, which is entirely open to the audience, with an excellent acoustic and onsite bar, so the perfect venue for this form of entertainment. Those taking part are chiefly actors, singers and musicians from the University and local community who have performed for ODT Productions over the years. Money raised goes to fund Out of Chaos, a theatre company founded by Mike Tweddle, Richard Darbourne (Oberon and Lysander in A Midsummer Night’s Dream 2001) and their colleague, Paul O’Mahoney.

one of the performers!

So life comes full circle and I can perceive some kind of resolution. My ‘life line’ has been a devotion to art, to language, theatre and dance. My energy has been spent contacting a vital force, reaching out and enthusing others as to its life giving energy. And this is the sort of immortality I believe in, when what you have done and what you believe in lives on in other people - immortality through others, which guarantees that the world, or your part of it, will continue.

We are accountable to the future, to those who come after us, who blossom when we have gone.

Appendix

Warning: I’m afraid this will not be a paean of praise for our beloved National Health Service, but a truthful account of some of my experience with the organisation.

Our beloved NHS, which is coping so magnificently with the present coronavirus pandemic has done an excellent job ‘sticking me back together’, for example, effecting a repair to a torn ligament in my leg in 1988. However, in my experience, general chronic conditions like neuropathic pain seem to exceed their competence.

For eleven years after the road accident I endured unhelpful drug treatments and injections in the throat, which often made me lose my voice, together with badly given acupuncture, unhelpful neurosurgery, ‘counselling’ and so on. I attended the Abingdon Pain Relief clinic until 1991 when, as previously mentioned, I was rescued by shiatsu, which allowed me to be relatively pain-free for about 18 months and drug-free until 2007.

A few memorably difficult experiences which didn’t help my pain:

While being treated at the pain relief clinic I was occasionally subject to hurtful criticisms such as ‘Any normal person would call this a headache’, this a comment from the head Pain Surgeon. Only once was I actually asked to describe the pain, but when I replied that it was ‘scything, searing, corroding, corrupting’, I was immediately rebuked by a different head surgeon for being ‘too poetic.’ I had fondly hoped that he would understand the surreal quality of pain, which is huge, all powerful, totally controlling, far beyond life’s everyday challenges. Where was his healing empathy, I wonder?

Another example of complete lack of empathy occurred during NHS ‘acupuncture’ treatments. When I admitted that I continued to invest in acupuncture on a private basis, the inept NHS nurse responded by saying ‘Oh, you want consultants in their Savile Row suits do you?’ I, like other patients I’m sure, was in much too vulnerable a state to be able respond adequately to her sarcasm.

I was also involved in ‘counselling’ sessions re-the pain which included memorable questions about how many times a week I masturbated etc.

In 2011, having endured a period of depression, I was considered for more drug treatments, although by then there was only one ‘pain killer’ I hadn’t already tried. I was assessed for Mindfulness, which I had myself considered, but rejected partly on the grounds that, as a disciple of Rudolf Laban, I had for many years experienced its benefits, chief among them, ‘living in the moment’. There were consultations about possible M.E., chronic fatigue etc., but these generally ended with a somewhat cursory, ‘her symptoms may in fact be related to her chronic pain disorder’.

As it says in a reputable American scientific journal, ‘Some people suffer from a type of pain so unbearable that words cannot describe it, which has no physical cause but which gets worse over time and which does not respond to normal pain killers …. It is caused by injury to the nerve fibres, resulting in incorrect signals being sent to the brain … Treatment with conventional analgesics is rarely effective, making neuropathic pain extremely resistant to treatment, which can cause extreme physical, psychological and social distress.’

In forty years, this has never been explained to me by any UK medical practitioners.

For two years or so (2013-2015) the procedure, Deep Brain Stimulation, was considered by the NHS chief Consultant Neurosurgeon at the John Radcliffe. I had paid to see him privately as I was receiving such confused information from a variety of NHS pain consultants, most of whom seemed to know very little about neuropathic pain and how it might be cured. However, the chief Consultant rejected D.B.S. out of hand, and advocated Occipital Nerve Stimulation (O.N.S) as being ‘more appropriate’.

By this time I had quite dropped off the edge as far as personal enthusiasm for potential new ‘cures’ was concerned, and became totally sceptical when the Professor enthusiastically recommended a TENS machine, which I had tried before but had put me in more pain than anything else. So it was interesting, from an objective standpoint at least, to watch O.N.S being eagerly followed up by yet more specialists, constantly assessing me, requiring reports etc., for another two years. I have copies of these reports, which were long, taking time, thought and analysis to put together, to this day. The Consultant Neurosurgeon was occasionally present at our brief encounters, and always optimistic about eventual results.

On January 5th, 2015, I was given what was called a ‘Comprehensive Neuropsychological Assessment’. (Neuropsychology: ‘a branch of medicine dealing with diseases involving the brain, nervous system and behaviour’). However after this, and apparently on the advice of this one Neuropsychologist, who had never seen me before and scarcely interacted when we did meet, ‘the surgical team’ made the decision not to give me O.N.S.

In a brief letter to my GP the chief Consultant Neurosurgeon claimed that it was made on the grounds that ‘Jacqueline had unrealistic expectations of Pain Relief’. He also claimed that the pain, ‘which is more widespread than first described, is too extensive to cover with O.N.S.’ Giving him the benefit of the doubt I should assume, I suppose, that he had not had time to read and digest the detailed and consistent reports that I had been submitting for over four years. My descriptions of the pain and its location and development had certainly not changed in that time. Ultimately the uncompassionate, totally unsympathetic way in which I was dismissed was very hurtful.

If the procedure had been medically approved and deemed appropriate, then why was the decision to proceed cancelled because of the patient’s ‘attitude’ at this one meeting? Or had it been a mistake to advocate O.N.S in the first place? If so, why wasn’t this acknowledged, and much NHS time, expertise and money saved? Why was it necessary to lay the blame so unsympathetically on my shoulders, while the system and people working for the system bore no responsibility?

Finally, an honest notification of NHS failure to help with my condition after almost forty fruitless years came in a letter from Dr Tudor Phillips MA MD FRCA FFPMRCA. ‘Unfortunately I do not think there is much I can add to her management as she has tried everything we have had to offer over the years … I am sorry that I am not able to be of more help at this stage.’

We know that the NHS is good at many things, but in my experience of over thirty years, compassion, which plays a major part in the healing process, is not one of them. Or was the cursory language of their general dismissal some kind of admission of the fact that they had obviously failed in my case? I wonder …

However, for thirty years I was able, despite the pain, to dance, choreograph and direct my own Theatre Company. I suppose, thinking positively, I should count myself lucky. There have been just one or two occasions when lack of confidence regarding the unpredictability of the pain and ensuing nervous tension have obliged me to cancel performance. And as I lie on the sofa meditating my fate this still causes some regret.

One example to get this out of my system: a group of 1960s University actors, some of whom are now media personalities in their own right, came together in 1988 to perform at the Playhouse. I had promised to dance to a Gershwin Prelude which I had enjoyed choreographing, but as the performance date approached did not have the courage to take part. This was for a variety of reasons, but it was ultimately the unpredictability of the pain that caused me to opt out. I know that I would have performed with feeling, that my choreography was gentle and attractive, in tune with the music; it would have moved the audience, and I was anticipating a positive reception which would have been a satisfying end to an active career as a dancer … Usually it is the well-directed cast that revels in all the applause! A stupid regret, I know, but it still plays on my mind.

Since 2010 the burning pain has grown considerably worse, true to the condition of neuropathic pain, (cf. American scientific journal quoted above), and I am now much weaker and more or less housebound. Unfortunately, the medical profession have been unable to help.

'Cela est bien dit … mais Il faut cultiver

notre jardin’ or ‘We must cultivate our garden’.

This is the last line of Voltaire’s Candide - a maxim

which has meant a lot to me throughout my life.

I now have three trees, with a bench to watch them

grow, in the University Park.

Saddest of all, perhaps, is that interaction with others, which used to be such an important and fulfilling part of my life, has become increasingly difficult. It had been my reason for living, for working and giving joy to others in the face of such overwhelming pain.

However, I think I can in all honesty say that I have been true to myself throughout, however arduous the path

So to return to the quotation we started with: ‘In common life your sorrow is a more or less dull pain, and its object – what it is about – remains a thought associated with it. There is no new depth of experience promoted by the connection. But if you have the power to draw out and give imaginative shape to the object and material to your sorrowful experience, then it must undergo a change. The feeling as finally expressed is a new creation, not the simple that was felt at first.’