Ideas for productions which have meant a lot to me are discussed later in this essay: Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale (1987 and 2008 productions); West Side Story (1988); two promenade productions: Jesus Christ Superstar (1994) and Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1995); four plays by Bertolt Brecht (1991-2007); five of Samuel Beckett’s shorter plays under the title We are the Last Five (1993); three of Shakespeare’s plays - The Tempest, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Winter’s Tale (2000-2003) and Christopher Marlowe’s Dr Faustus (1966 and 2004 productions).

Having staged a performance of Stravinsky's The Soldier's Tale under my own name in 1987, I formed the Oxford Dance Theatre in 1988 to direct a production of West Side Story at the Newman Rooms, the Catholic Chaplaincy, St. Aldates, Oxford. This had a cast of forty singers, dancers and actors, drawn from both city and University, many of whom went on to careers in the worlds of professional theatre, dance and the media generally.

In this photo I've been dancing in costume as a 'live model', here

portraying Katherine of Aragon, for art students at Didcot School

to draw and paint me. This photo of me talking with the art

master and students featured in the TV film made in the '80s to show how dance helped me cope with pain.

Over ten years the company performed a variety of musical theatre pieces including Guys and Dolls, On Your Toes, Chicago, Blues in the Night, Jesus Christ Superstar, Pink Floyd's The Wall, Fiddler on the Roof and Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods, all in the Newman Rooms. Productions then began to take us elsewhere, one of the first being A Portrait of Gershwin. The composer’s work in ‘Music, Words, Song and Dance’ was performed at the Jacqueline du Pre Music Building, St Hilda’s College, in 1994.

As I wrote in a programme note for the little known musical On Your Toes (1991): ‘Drawing its casts from all walks of life – students, teachers, civil servants (Tax Inspectors!), retired people, the unemployed etc. – the company has gone from strength to strength, performing both well-known and rarely seen musicals requiring a lot of talent. One of the latter is the musical On Your Toes in which the lead is required to play classical piano to concert standard, dance tap, jazz and ballet, while singing and acting throughout. Anthony Chalmers amazingly has all the required talents; he is a Medical Student in his spare time …’

In the early ‘90s I began to direct straight plays, the first of these being T.S. Eliot's Murder in the Cathedral, at St Mary the Virgin Church, High Street, Oxford. I was at the same time entering a very different world, that of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, with a production of Happy End in New College school, where I was then teaching drama. The priests, female chorus and four knights in Murder in the Cathedral used expressive movement throughout the church to communicate the feeling of Eliot’s poetry, while in Happy End the group of dancing gangsters added humour and vitality to Brecht’s already highly entertaining text.

I mention these two pieces because, although Murder in the Cathedral would definitely be called a ‘straight’ play, in both this and Happy End (itself not exactly an example of ‘dance theatre’), the physical elements of performance, movement, sensitivity and physical characterisation were of vital importance to me and remained so throughout the history of the company. Influenced by my study as a dancer/dance teacher of the theories of Rudolf Laban, I interpreted the latter’s ideas concerning the language of movement in terms of the actor’s understanding and ability to portray character and relationship. These concepts were to be the basis of my work with ODT over twenty-one years. They are considered in more detail in the auto-biographical chapter of this book.

I cannot resist including here a comment from Richard Darbourne (Lysander in MSND 2001) who obviously appreciated at least one aspect of my physical approach: ‘I don’t think I can recall a better example during my time as a student doing drama where the experience and process quite so matched the feeling of the work itself as ODT’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I put this down to the excellent physical body stretching and exercising that preceded each rehearsal and performance. It felt very much in keeping with the ODT ethos and something I took with me to later work. You were not merely committing mind and voice to a rehearsal but rather preparing for it properly with body as well. I think the process meant you could really get in tune with the piece and it was brilliant prep for playing one of those erratic and dreamlike Lovers. Lysander was a lot of energy and prancing about.’

Introducing Moving Pictures, a dance performance with young

people, at what was in the '80s a thriving St Paul's Arts Centre,

(now Freud's cafe/bar) Walton Street, Oxford

Although the physical aspects of the actor’s performance have always been of prime significance for me, the nature, use and transformation of space have been of equal importance. Instinctively suspicious of proscenium arch theatre, I have relished directing at a variety of venues in Oxford and elsewhere, most recently at The North Wall theatre and Holywell Music Room for my last production of The Soldier’s Tale (2008), but most frequently at the Newman Rooms (1988-1997) and The Old Fire Station theatre (1998-2006).

The majority of Oxford Dance Theatre productions during the first nine years of the company’s existence took place in the Newman Rooms, which, as a large, totally unadorned space, were open to many different types of staging, including ‘end-on’ and traverse. They were great too for promenade performance, with the audience accompanying the actors as the crowd in JCSuperstar or providing a rock concert atmosphere for The Wall.

In the early ‘90s, however, we were beginning to stage productions which could not legitimately be called ‘Dance Theatre’. So I decided that the group should adopt the title ODT Productions, the initials remaining in an attempt to keep something of the company’s original inspiration… at least for its founder!

After 1998 the majority of performances took place at the Old Fire Station theatre, which, until it became too expensive and unwieldy to transform, could be used in different ways to convey many interesting atmospheres. I directed Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls (1999) on the small end-on stage, which served well to illustrate the confinement of the characters’ lives, as it did to represent Faustus’s study - although his travels were realised with an imaginative use of video footage above the stage, giving us considerable freedom to express change of location. I created an area as close as possible to ‘in the round’ to represent the island in The Tempest - then used the theatre in traverse for A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Winter’s Tale, reinforcing the sense that both are ultimately about journeys.

We also performed in the Burton Taylor theatre (perfect for We are the Last Five, a sequence of Samuel Beckett’s shorter plays), churches, bars, clubs and concert halls - in each case the space that I thought would be most conducive to the success of the piece. I overcame my suspicion of the proscenium arch stage to direct just one production at the Playhouse for the Oxford Operatic Society; this, as described in the auto-biographical section of the book, was Bernstein’s Candide, based on Voltaire’s eighteenth century novella of the same name. I justified the use of proscenium arch as being true to the eighteenth century roots of this text.

So in general I would much prefer to convert somewhere which seemed to me as though it would ‘fit the bill’. In fact, when reflect on it now, the space was often the inspiration for my choice of performance. The Round House was first advertised as somewhere ‘which seeks to bring people together rather than just sitting them down in rows’; this certainly appealed to me, and was one of the reasons Lord Bill’s performed there in the 70s!

As actor Robert Bristow (discussing my production of The Blue Angel, which took place in a small LGBT Nightclub in St Michael’s Street) agrees: ‘A crucial element of production was always the choice of venue … Northgate Hall was designed in an old-fashioned style – an early 20th century community hall with a small platform for a stage with no wings. These elements meant that it provided the perfect backdrop for Brecht’s cabaret style pieces, with a tinkling piano expertly playing Weill’s music as accompaniment to the silent movie style drama threading them together.’

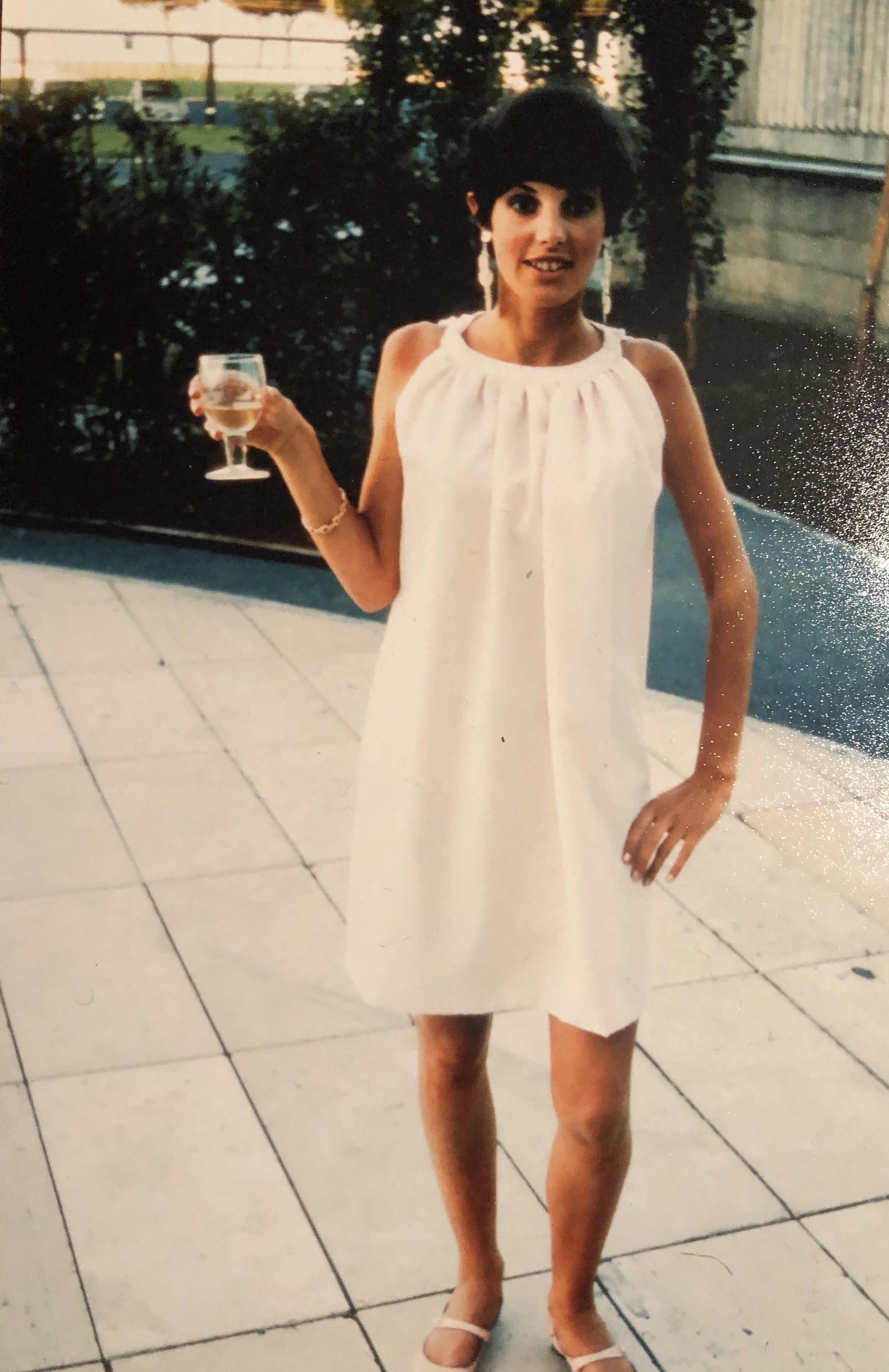

Time off(!) from the Burton-Taylor film version

of Dr Faustus, made at the Cinecitta Studios,

Rome, in 1966.

I’m sure it was the fact that I had always had an affinity with dance (and had in my early career danced with a company working in many different performance environments as we toured schools, colleges and small theatres) which made me ultimately aware that the atmosphere of a piece can always be enhanced by its location. I think Walter Gropius was right when he said that ‘Architecture changes us’, an idea which in this context reflects as much on the audience as on the actors.

Later titles performed include Sheridan’s The Rivals, Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie and A Woman of No Importance by Oscar Wilde, all performed on the end-on stage at the OFS, which suited the confined nature of their characters and themes. But my interest in working in different spaces never left me. ODT’s four productions of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, which had started with Happy End in a school hall in 1991, all took place in different venues. We performed The Blue Angel, as described above by Robert Bristow, in 1995 in an LGBT Night club, The Threepenny Opera at the OFS theatre in 1998 and The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui in the more august setting of Headington Theatre in 2007.

With The Resistible Rise the company had existed for twenty years. I had by that time directed many of the plays and musical theatre pieces which interested me, and was considering bringing things to a close. However, the company’s final production, in May 2008, was a reprise of The Soldier’s Tale, which we had first performed at the Burton Taylor Theatre in 1987. As described in the relevant chapter, this came about in response to a request by Chris Windass, lead violinist with the Adderbury Ensemble, who had played for my first staging of the piece (describing it as an ‘inspirational’ experience).

Another important aspect of ODT’s ethos was that it always sought to bring together local people and members of the University who might otherwise have little opportunity to meet. This proved to be a great boon, not only in terms of breadth of talent, but also because those taking part so obviously relished the collaboration. Cast members were sometimes former or current professional actors, and every year one or more young people went on to become involved in professional training and performance themselves.

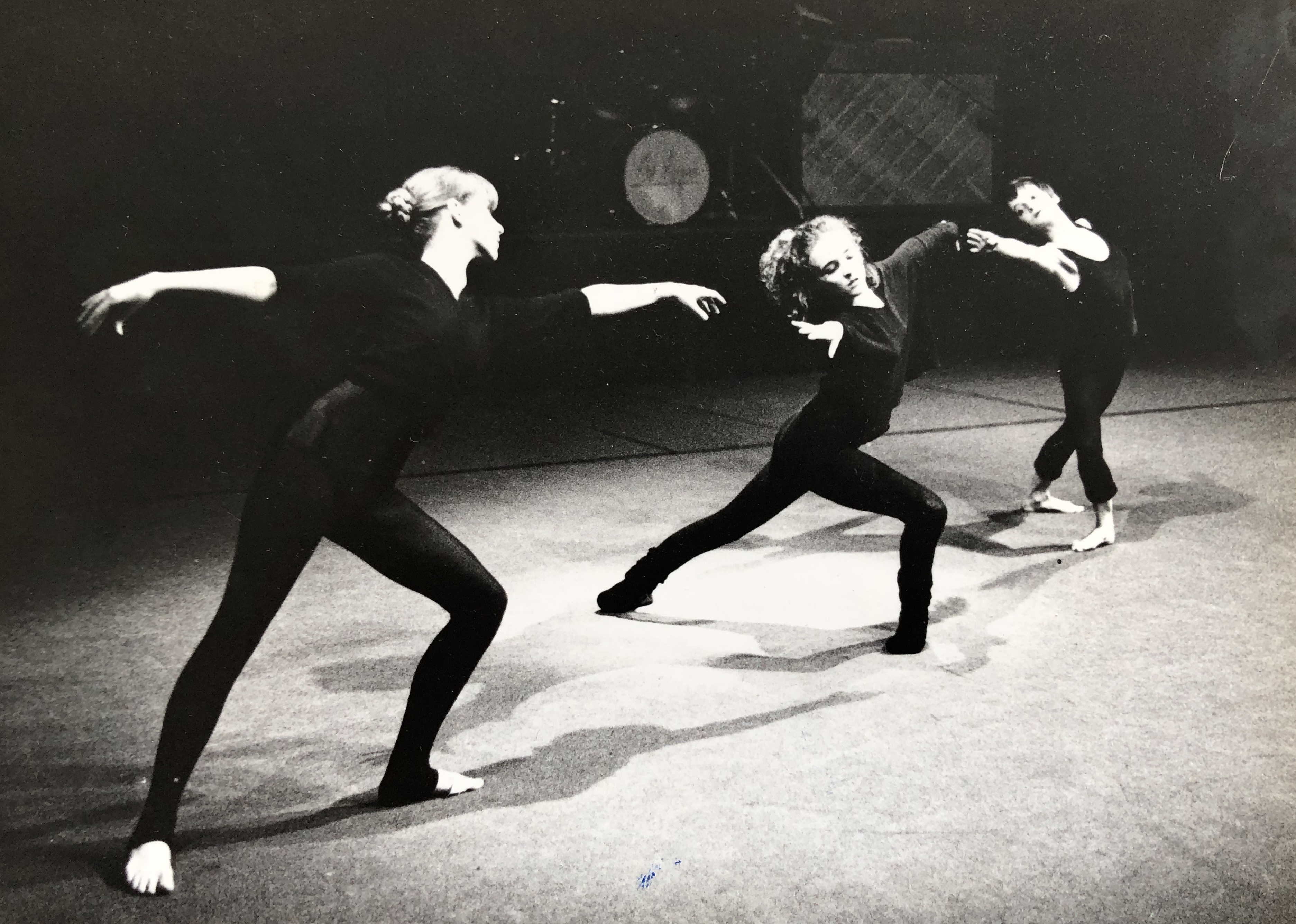

Students dancing Equilibrium, one of the sequences I

created based on different aspects of The Body,

performed at the Round House in 1975.

Richard Darbourne (Lysander) was then a student of Theology at Pembroke College. He comments that one of the things he relished most was ‘discovering friends and an Oxford that existed outside of the University, which I will always be grateful for’. Mike Tweddle (Oberon), studying English at Wadham College, speaks poetically: ‘I imagine the huge joy and satisfaction of belonging to a company of people from different generations and backgrounds – the most diverse and generous company I got to be in during my time in Oxford. As well as being a rich personal experience, the diversity also made the art better – I’ve taken that principle into many future projects.’ Meanwhile ‘Townie’, Marion Baker, (Jenny Diver in Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera 1998) says that one of the reasons she loved playing the part was because it gave her ‘the opportunity to get to know people I would otherwise not have met, students and local people alike.’ Another ‘townie’, Mark Eariss, (The Tempest/MSND), proclaims that ‘working with local students added an energy which was quite infectious.’

A number of ODT performers have gone on to become members of ‘the profession’. To name but a few: David Allard, (Narrator in The Soldier’s Tale 1987 and A-rab in West Side Story 1988) was a student of English at Balliol College; he is now a Producer/Presenter for BBC South. Senior Theatre Practitioner at the Globe is Adam Coleman (original Soldier in The Soldier’s Tale, Action in West Side Story and Nathan Detroit in Guys and Dolls 1989), who was at that time a drama student at Oxford CFE. Emma Kershaw, (Anita in West Side and Miss Adelaide in Guys and Dolls) studied languages at Oxford Polytechnic; she has since become a very special Choral Artiste. University student David Schneider (Glad Hand in West Side) is a well-known comedian, actor and writer, recently collaborating on the script of the satirical film Death of Stalin.

Having been a pupil at Lord Williams’s school, where I taught him dance-drama in the sixth form, Robert Bristow went on to train as an actor/singer at Guildford School of Drama. After his return to Oxford, Robert surely deserves a medal for the list of major roles he played for ODT Productions. These include Pilate in JCSuperstar (1994), Pink’s Alter Ego in The Wall (1995), an actor in Beckett shorts (1995), the Baker in Into the Woods (1997), Peachum in the Threepenny Opera (1998) and Arturo in Arturo Ui (2007). He has for some years now been Manager of the Burton Taylor theatre.

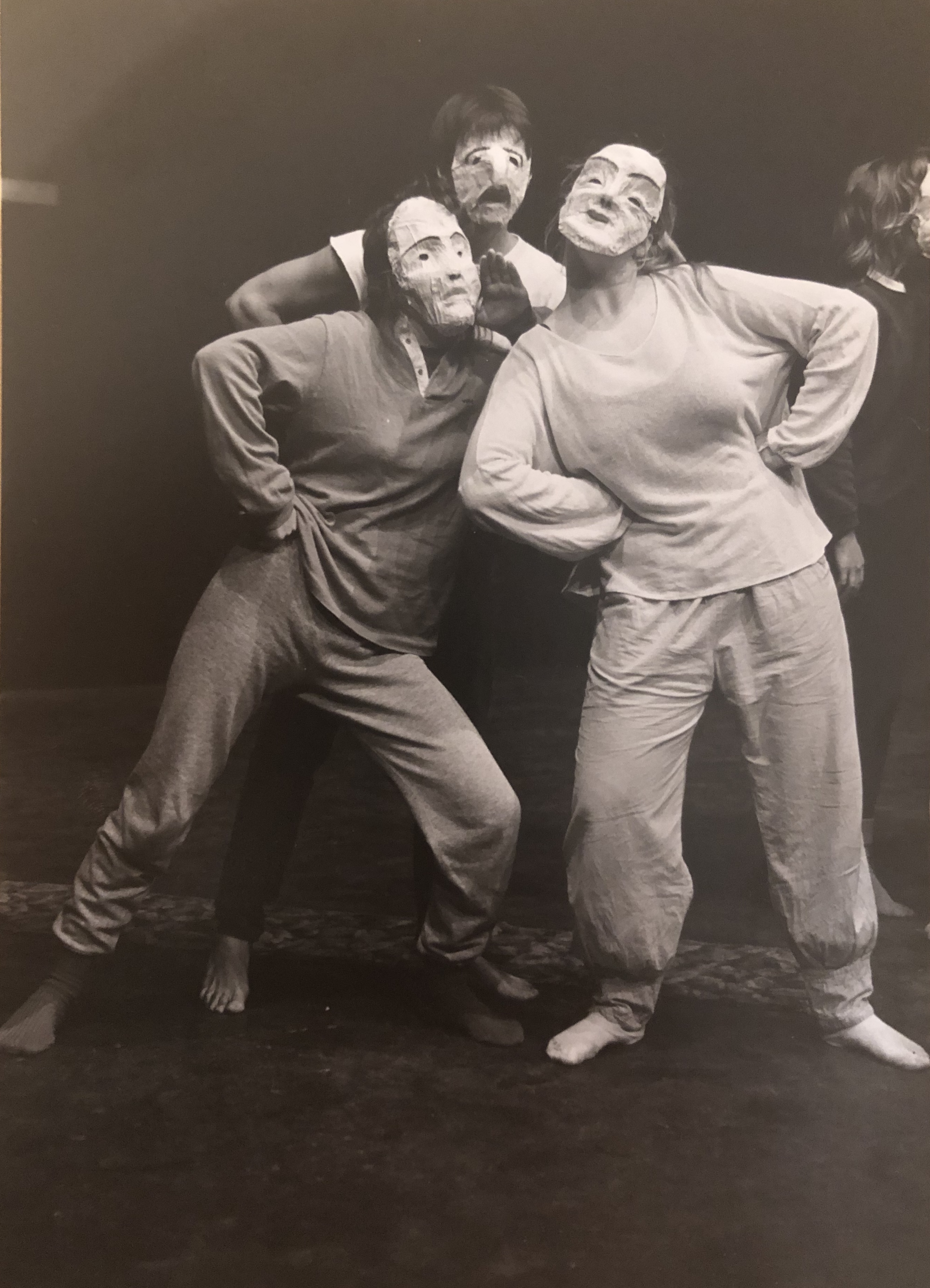

Masked characters from our dance-drama, Fission Trips,

(a take on the nuclear holocaust!) at the Pegasus Theatre,

Oxford. This was created mid-80s, at the height of the cold war.

Prasanna Puwanarajah, formerly a Medical Student at New College and Caliban in The Tempest (2000), is now a successful free-lance actor, writer and director for the Royal Shakespeare Company and National Theatre. Mike Tweddle (Oberon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream - 2001) now directs at The Tobacco Theatre, Bristol, where his productions have included a highly praised View from the Bridge and more recently A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Richard Darbourne (Lysander) is Producer for Ambassador Theatre group productions; he also runs his own very successful production company with shows world-wide.

Alex Nicholls (Quince in MND, Leontes in The Winter’s Tale – 2002 - and Sir Anthony in The Rivals, 2003) is a teacher, experienced director and actor, and, like Robert, a member of the Oxford community. After appearing in many plays for ODT Productions, Alex formed his own successful company, Tomahawk, which delights large audiences with productions of Shakespeare at the Castle every summer. Another member of the local community, Marion Baker (again involved in several ODT shows, her biggest part being that of Jenny Diver in The Threepenny Opera, 1998), now leads the Young Company at the Theatre by the Lake in Keswick. And Kate Saffin, (the Giant in ODT Into the Woods and Pink’s Mother in The Wall) now writes and performs (on a boat!) in her own company, Alarum Theatre, at a variety of venues throughout the UK.

The Soldier in my 2008 The Soldier’s Tale was Tom Bateman, at that time a student at Cherwell School. Soon after graduating from RADA, he performed to huge acclaim as Shakespeare in the West End production of Shakespeare in Love. He has since taken on many roles in film and television, recently playing the lead in ITV’s Beecham House. At time of writing he is now a member of the Kenneth Branagh Company.

Chris Walters (one of my first dance-drama students at what was then Culham Teacher’s Training College, Abingdon) taught Drama at Lord Williams’s and then Stowe school. Chris very often contributed his talent to ODT, playing most notably an engagingly pathetic Mr Cellophane in Chicago (1991), a superbly comic Trinculo in The Tempest and surreal Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale. He is, at the time of writing, directing a group of Afghani and Iraqi refugees in a production of the Caucasian Chalk Circle on the island of Lesbos.

There are so many others I could have mentioned – I hope they will forgive me for not having the space to refer to everyone in person.

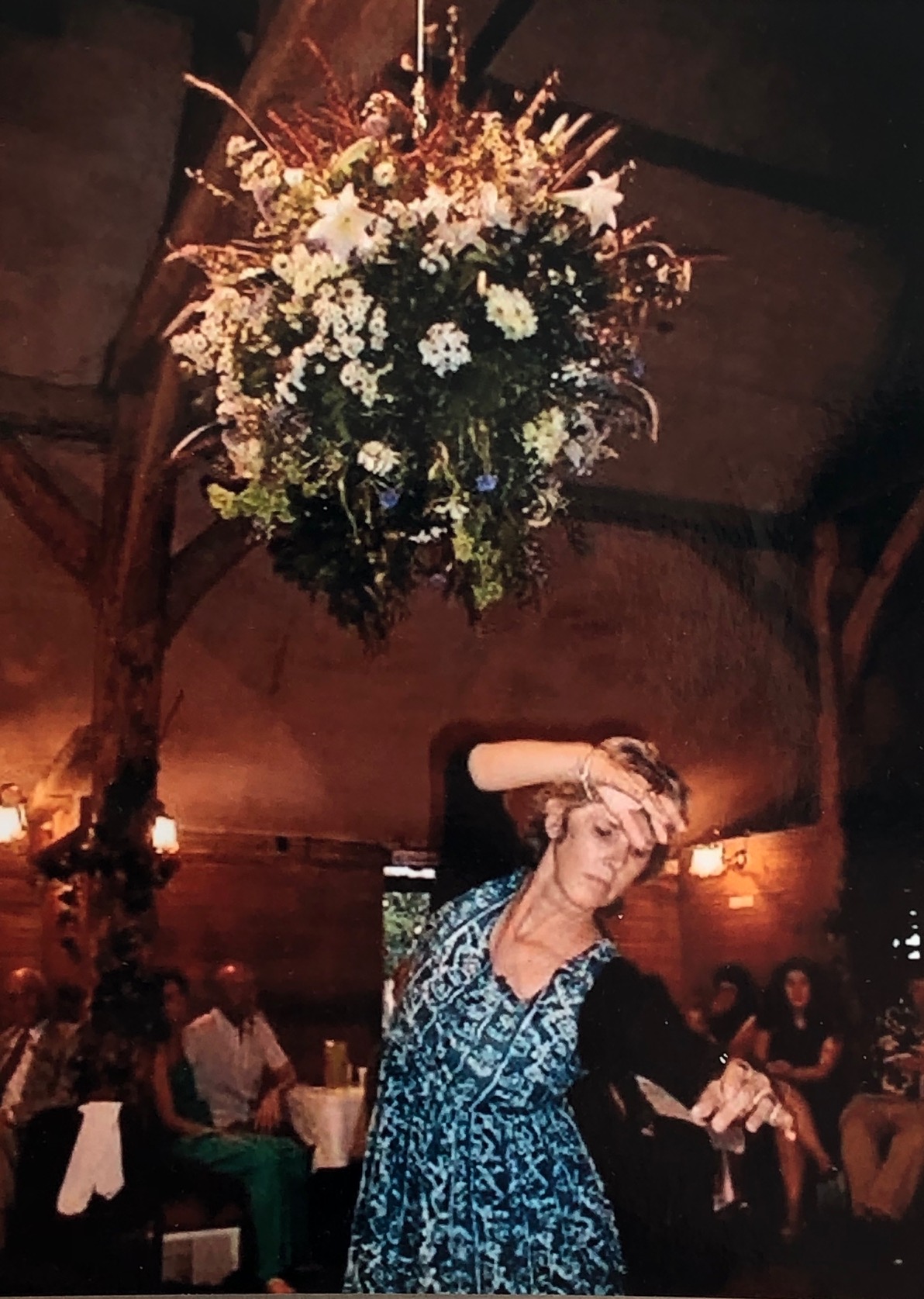

Me performing one of my favorite dances,

choreographed to one of Gershwin's Preludes,

at the celebration of a friend's wedding,

late 1990s.

A vital aspect for me was that the drama/dance/education link should be maintained, with titles in later years often taken from the syllabuses of AS/A Level English Literature/Drama and Theatre Studies courses. From a pragmatic point of view this always ensured ‘bums on seats’, while fulfilling the ideal of providing the younger generation with the opportunity for contact - maybe their first - with live theatre. Bruce Young, Head of Drama at Burford Community School commented on the traverse production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream: ‘For some of our students this was the first time they had seen a live Shakespeare production and the feedback was very positive. They were especially impressed by the intimacy of the production which helped them to understand “what was going on”’.

Each production has been a very different experience, enjoyable and educational in the broadest sense of the word. Convinced that artistic collaboration is a powerful vehicle for growth, both on a personal level and communally, I consider myself privileged to have shared in the many rewards that this brings. I remain firmly committed to a belief in the intrinsic value of artistic experience for everyone. And for me the work involved in creating performance with a group drawn from a very wide social spectrum has the profoundly important value of actively fostering an ideal of community.