Supposedly dancing as a 'sprite'

for the film version of Dr. Faustus,

I remember spending most of my time

in the dressing-room supporting this very heavy wig!

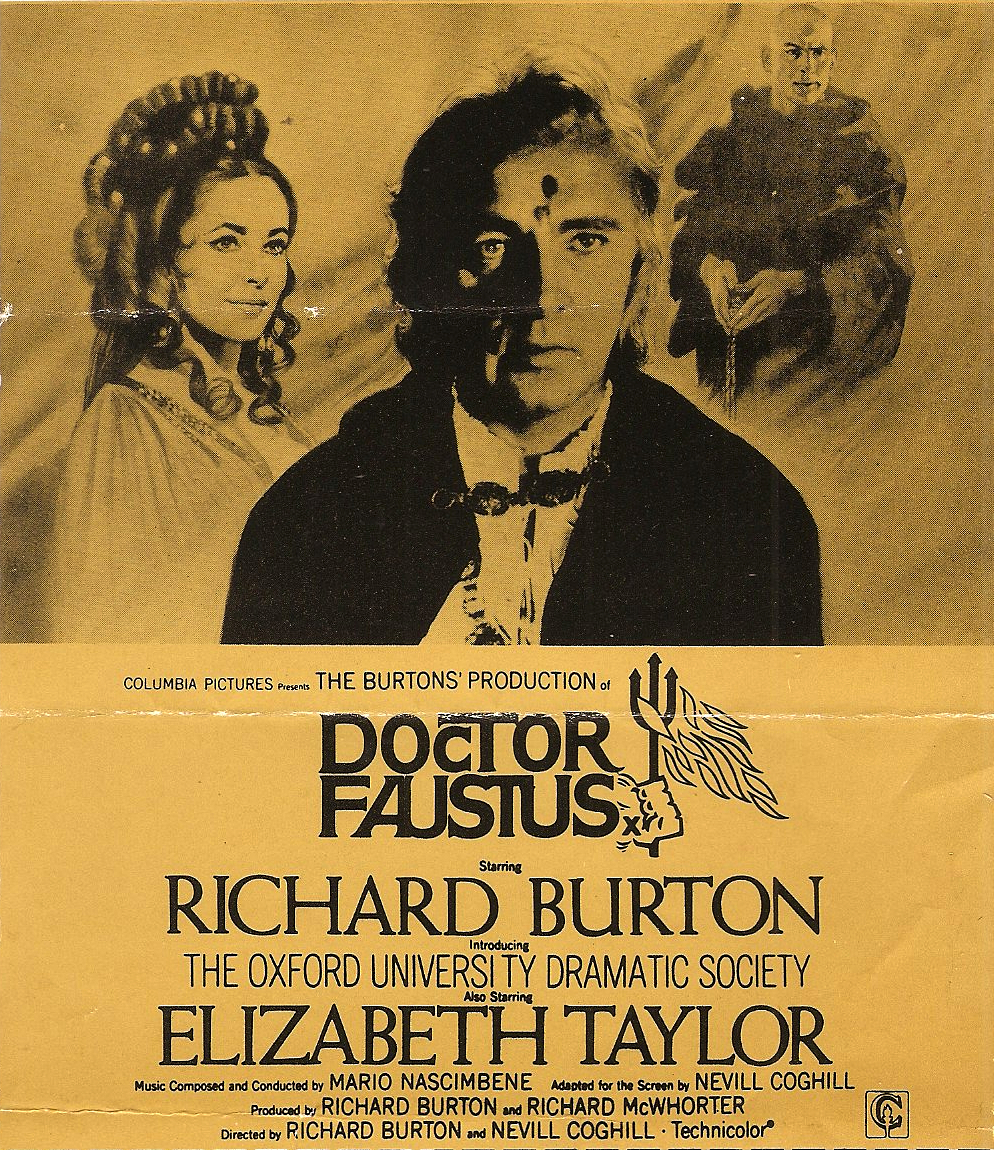

As President of the O.U. Ballet Club for two years, during which time I had choreographed many student plays and dance performances, I guess I was the natural choice to choreograph the Nevill Coghill/Burton Taylor production of Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus. The play was due to take place at the Playhouse with a supporting cast of students in the second term of my final year. I wonder if, nowadays, I would be permitted to undertake this adventure at such a crucial stage in my academic career?

I started working with the composer, Kenneth Jones, on ideas for the play during the summer of 1965, which I very much enjoyed. It was the first time that I had had the privilege of working with a live composer and I found it fascinating. At the beginning of Michaelmas term I auditioned for six girl dancers, four of whom would eventually come from LMH, and for one male student to portray Alexander in the scene, Alexander and his Paramours, conjured by Faustus for the Emperor of Germany. Hilary term 1966 I started rehearsals for this and two dances for Devils, played by the six girls. The Seven Deadly Sins were also highly stylised, moving behind vast shields painted to represent each particular vice.

As choreographer one can be quite distant from the main action of the play, as I was in this case, working with a small corps of dancers who were to make only rare appearances. I had the occasional pre-show meetings with Nevill Coghill and Nick Young, Assistant Director, but knowing the context of each dance, working with especially composed music and familiar with the ideas for stage design, setting and costumes, we were very much left to our own devices.

I was standing next to Richard and Elizabeth, with Mephistophilis, (Andreas Teuber)

on one side, and Nevill Coghill, the Director, behind.

And looking back, I can honestly say that, when the Burtons eventually arrived a few days before curtain-up, I wasn’t at all overwhelmed by the two great stars’ ‘glamour of a knock-out voltage’, to quote Kenneth Allsop, who presented a BBC TV news feature during the last week of rehearsal. For me the whole Faustus event was very enjoyable, but I felt from the beginning that the mere fact of including two celebrities in the cast would in no way guarantee the play’s artistic success. Somehow I didn’t really feel very ‘artistically involved’ myself. I remember not even making the effort to stay for cast photographs after a final rehearsal involving the Burtons (I wanted to be with my boyfriend!), despite the kudos this would undoubtedly have brought. The photos then taken of the Burtons and cast were displayed – for many years, actually - in the Playhouse foyer.

Professor Coghill’s production was certainly lavish, extravagant in its use of costume and set, but very traditional and almost entirely static; just actors speaking their lines, with little physical interest. It made little or no real contact with the audience. Of course Richard Burton was outstanding as Faustus, his voice reverberating with emotion in the play’s great speeches, but the critics were waiting to see Elizabeth Taylor making her stage debut in ‘the greatest non-speaking part in the world’. And they had to wait a very long time. Helen of Troy, consummate vision of Faustus’s dreams, makes her brief appearance for ‘the kiss’ only towards the very end of the play. I was given the task of choreographing Elizabeth’s entry, but the kiss itself was left to the couple, who had been happily married for two years at that time so no probs …

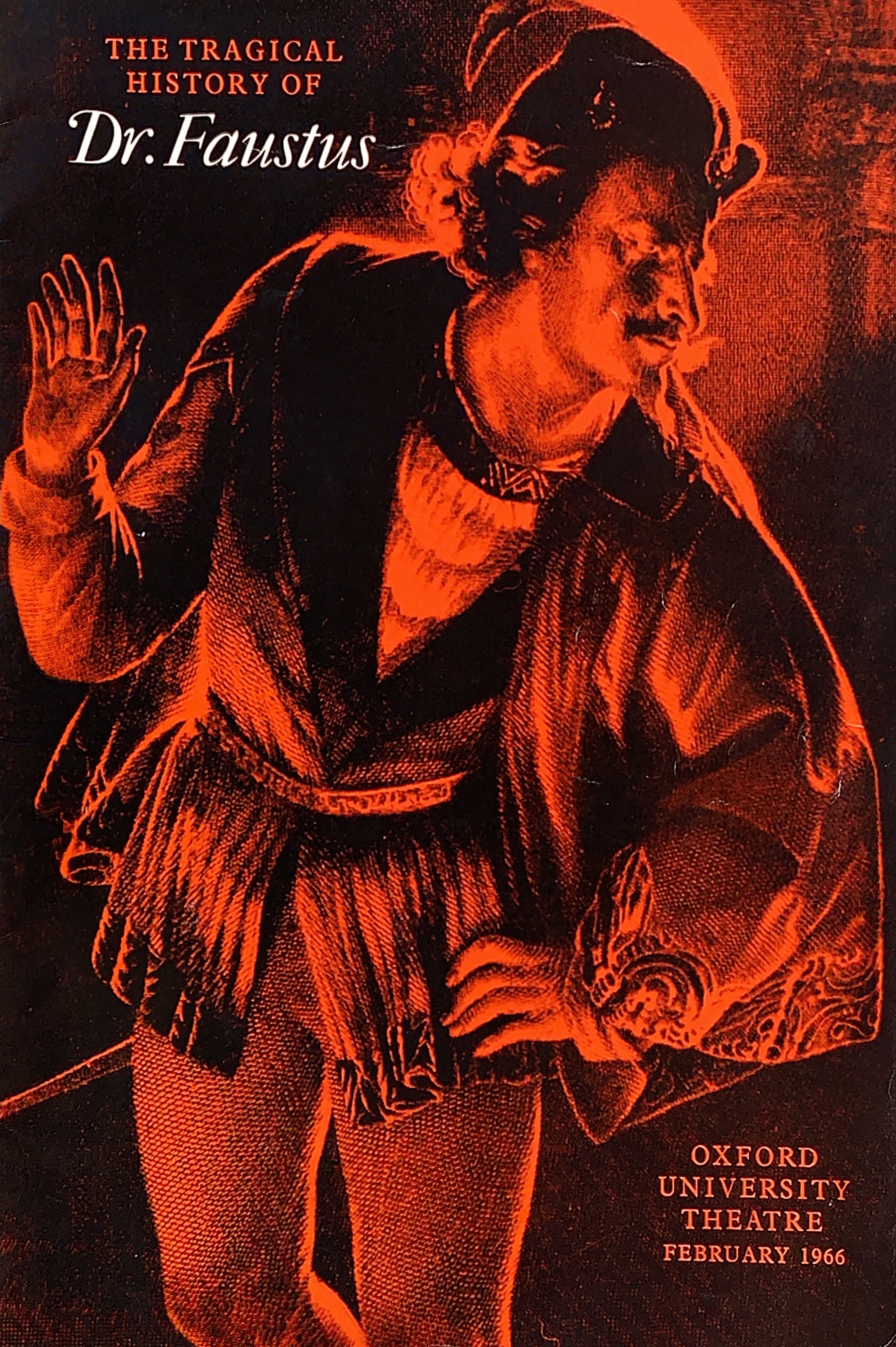

based on the 1864 drawing of Mephistophilis

by artist, Friedrich Pecht.

Writing in the Oxford Times, Don Chapman proclaimed, ‘We have a foretaste of the visual splendour of Helen’s reincarnation in the idyllic handling of the resurrection of Alexander and his Paramours. Then the great lady is before us and gone.’ As choreographer I was responsible for the ‘idyllic handling of the resurrection of Alexander and his Paramours ’, so this comment seemed as much a compliment for me as for the ‘great lady’, which was heartening!

Elizabeth would spend the time until her entrance in her dressing room, at the last moment venturing into the wings accompanied by her wardrobe mistress, her make-up artist, hairdresser and bodyguard. According to critic Felix Barker, she ‘made her entrance… on a cloud of property smoke and through a trap door’ and crossed the stage for ‘the kiss’, while her attendants would walk round the back of the stage to gather her up and take her back to her dressing room. Whereupon the critics left.

The production was almost universally panned, with such choice comments as: ‘The seven Deadly Sins are paraded before Faustus. Boredom was not among them. It should have been. It had pride of place.’ Arthur Thickett, Daily Mirror.

However Richard and Elizabeth continued undaunted and were certainly very generous to members of the cast during the week of performance. They hired a floor of the Randolph Hotel where they would extend hospitality every night after the show.

They had both just acted in the film version of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, so Elizabeth was more than usually voluptuous, having had to put on weight for her part, and Richard smoked and drank his way through rehearsal – even at ten o’clock in the morning he would be saying his speeches with a full glass and ciggie in hand.

Burton as Faustus with the Seven Deadly Sins,

all bearing unwieldy masks ... this presented

something of a creative challenge to me as choreographer!

Still hoping to raise money to extend the Playhouse (one of his original reasons for coming to Oxford), Richard went on to direct a film version of the play with the same student cast at the Cinecittà film studios, Rome, in the summer of 1966. Together with the other dancers, I was cast as a sprite, wafting through very manicured ‘woods’. I had actually to be on set only a few times, so enjoyed the experience as a free holiday with fellow students in a beautiful city not too far from the sea. Memories include endless waiting in the sunshine, wearing very baggy, body-concealing pink tights and leotard and supporting for hours a glamorous, enormously heavy wig.

Quite unexpectedly, however, Lindsay Kemp, who had been teaching mime to Oxford students as part of the Ballet Club programme 1965/6, was also dancing in the film. It was superb to meet up with him and his boyfriend, the blind dancer, Jack, and see something of Rome’s bohemian life.

Like the theatre performance, the film was not well received and made little money, so actual plans for the Playhouse extension were never realised. However we do have the gift of the Burton Taylor theatre, which, since the 1980s, has provided an excellent small space for student and alternative theatre.

As stated in the relevant chapters, I used it for my very first production: The Soldier’s Tale in 1987 and for We Are the Last Five, Samuel Beckett’s Shorter Plays in 1993. It suited both projects admirably.