Bertolt Brecht is undoubtedly the author who featured most frequently in the history of the Oxford Dance Theatre. I studied Brecht during my M.A. course at Birmingham University, when I became interested in left-wing/Communist theatre (USSR writers such as Vakhtangov and Meyerhold), and very much enjoyed what I read. I wasn’t aware of any stage performances of Brecht plays in the ‘60s, so I was only able to read the authors on the page.

At that time a Socialist myself, of committed Socialist parents, I was drawn to Brecht’s political ideas. And, as with Beckett, I particularly liked his theatricality and individualistic ways of working with the medium.

Brecht’s theatre is often described as ‘naively didactic’. In his theatrical writings, of which there are many, he wrote that, ‘Art must change conditions, ways of thinking, people’s behaviour, the world.’ It was very much a theatre of ideals; what he was trying to teach was a Marxist view of the world: the evils of greed, the unfairness of society, an abhorrence of the effects of war, all of which of course he had witnessed in twentieth-century Germany.

In 1997, when I was doing research for my production of The Threepenny Opera, I read an article by Martin Woollacott about what he called the ‘Asian Storm’ and was aware that very little had changed from the 1930s. Woollacott vilifies the ‘incompetents, fools and knaves, sometimes cheats and thieves’ running the city of London… ‘We get London merchant bankers, men who may well earn a third of a million or more a year, explaining unctuously on television that in order to avert a crash, many billions will have to be paid to South-East Asia. Who knows who will be screaming for help next?’ He continues, ‘for those in the right places, it seems, capitalism is all gain and no pain … the thousands of business men and financiers, east and west, who made these decisions that created the present crisis, have damaged the rest of us but not themselves.’

As we know, worse things have happened since, the most obvious being the Crash of 2007/08. These cataclysmic financial events seem unstoppable. And inequality continues unabated; I read recently in the Daily Mirror, ‘The average pay of FTSE executives was £3.9m last year. That is 321 times more than someone on the minimum wage, 217 times more than a car worker and 121 times more than a nurse. Studies show that unequal countries have higher levels of mental health issues, obesity and drug addiction and lower social mobility and trust.’

The writings of one German author were hardly likely to put an end to financial inequalities, but this gives continuing interest and validity to his work, doesn’t it?

Being concerned with the evils of society rather than the peccadilloes of individuals, Brecht’s plays deal with large scale events, so much so that the term ‘epic’ is applied to them. However, they are not devoid of humour; on the contrary, they were described by Lee Strasberg as ‘exciting, colourful, enjoyable and moving’. These elements can be summed up with the term ‘spass’ or fun, encompassing music, humour, vitality, all aspects of theatre favoured by Brecht and all of which very much appealed to me.

Another key element that I really liked as a dancer, was Brecht’s belief in a ‘demonstrating’ style, the actor not identifying with his role but ‘showing’ him or her to the audience, who would then judge rather than believe in them. Brecht was definitely anti-illusionist, feeling that the process of ‘showing’ itself should be made quite clear. So no attempt would be made to provide a naturalistic environment, and no elaborate set to create an illusion of reality. However, props and costume were important, especially those for working and eating, which give a kind of truth to the characters portrayed.

Equally important for me as a dancer was Brecht’s proposal for a ‘gestic’ theatre; here the expression of an attitude can be seen in a single action or individual movement, or in the physical relationship between characters on the stage. With Brechtian stylisation, ‘gesture’ achieves an importance far beyond naturalistic incident, since every movement serves a meaningful, practical yet expressive purpose.

So it becomes important to restrict both performer and movement to the ‘essential’, again as I would do naturally as a dancer. Actors in Brecht’s plays might well be described as ‘cartoon-like’, portraying simplifications of reality, heroic, comic, wicked, whatever. This cartoon-like style is a vital part of Brecht’s ‘alienation’ or distancing effect. As in dance, clarity of movement, expressive and meaningful use of theatre space, quality of individual body shape and tension, together with clearly defined relationships between players are all important.

There is no attempt to conceal theatrical devices: sources of lighting are fully exposed and actors, together with stage management crew, should be seen working them.

Ensemble playing is vital; all actors support each other fully; there are no stars or ‘celebrity’ performers! I would hope I have adhered to this during sixteen rewarding years of directing Brecht’s plays …

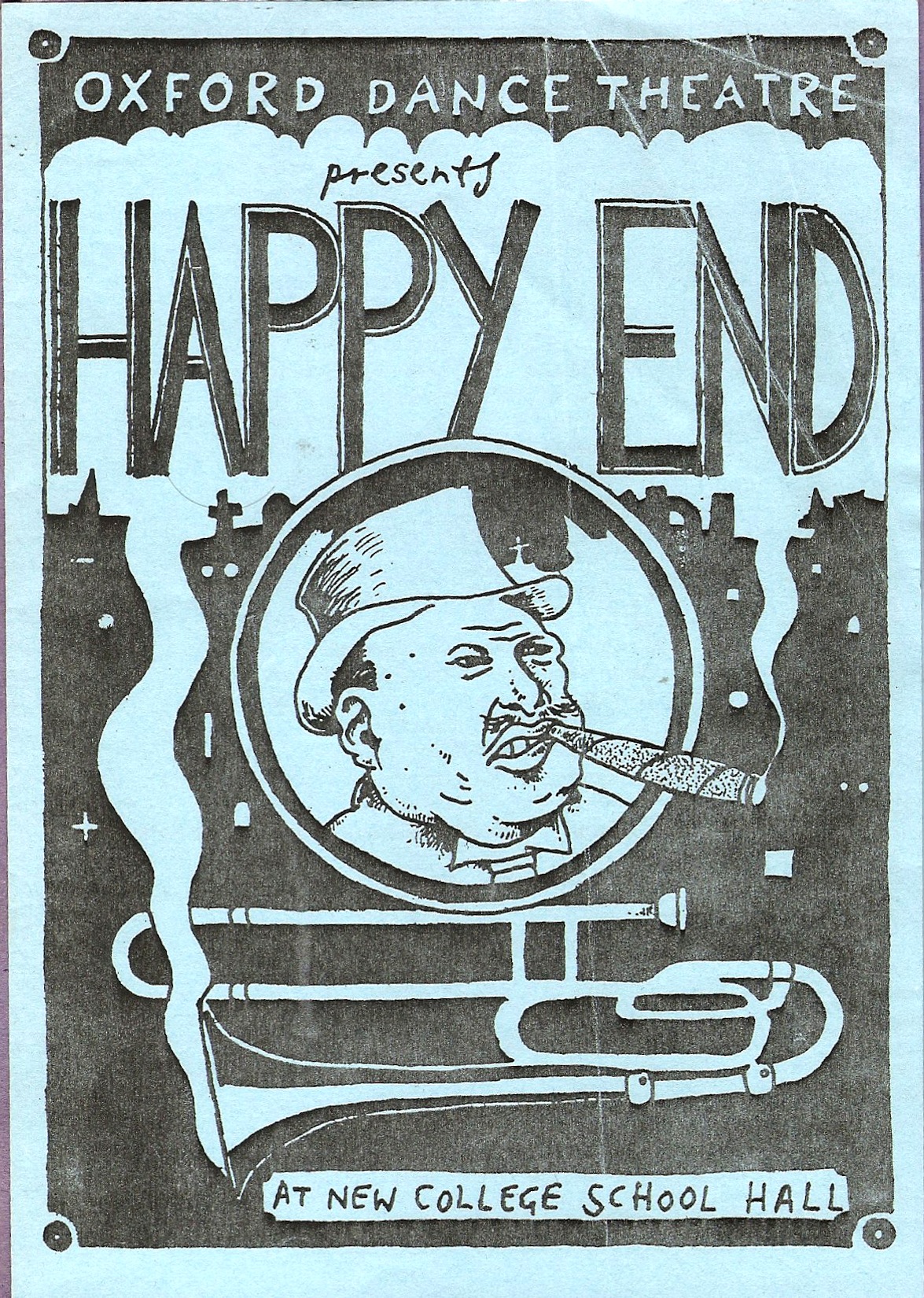

Happy End

Happy End was first produced in 1929. It closed in Berlin after seven performances and then played on Broadway for seventy-five.

Nineteen ninety-one was the first year I experienced some, (although sadly all too brief), relief from my neuropathic pain via shiatsu, so I had the energy to direct two theatrical events per year rather than just one. As intimated, I had enjoyed learning about Brecht at university, but there had been no opportunity to become involved practically in his work. In 1991, however, having by then garnered five years’ experience as a director/choreographer, I finally decided to try my hand at staging one of his plays. I still wanted to keep the musical element of my theatrical identity, so thought I would direct Happy End, a piece written by Brecht with composer Kurt Weill, whose music and songs characterise so much of the playwright’s work.

A bit about the play, thought to be at the root of the much better known musical, Guys and Dolls:

Attractive, charismatic Lieutenant Lillian Holiday of the Salvation Army in Chicago, falls in love with Bill Cracker, dapper leader of a band of gangsters led by a daunting female, the Fly, or Lady in Grey. There is much ‘spass’, action and interaction between these two groups, before the final political point is made by the Fly, ‘Blasting open a safe is nothing – we’ve got to blast open the big gang that keeps the safe locked. So slip on your brass knuckles and learn where to hit! Robbing a bank is no crime compared to owning one! The world belongs to all of us – let’s march together and make it our own!’

I was refused when I applied for rights to do the piece since I could not afford to perform it with full orchestra as required by the Brecht Estate. However, very fortunately, I had got to know David Maw, Music Lecturer at Oriel College, who had been interested to play for the musical, On Your Toes, which we had performed in 1990 with just two pianos as accompaniment. David was fascinated by Weill’s music, and conscripted as M.D., was happy to create and write out a full score for all parts from a basic piano version located in the University Library. I can’t thank David enough, as I know that this caused him a few months of intensive labour!

Although we both knew who we wanted for some of the characters, we had for some reason left choosing the principal female role until the beginning of our performance term, Michaelmas 1991. But, fortunately for us, student Zoe Willis, the only auditionee for the part of Lillian, was superb. I remember David and I were both delighted; there was no competition. Zoe went on ‘to act and sing with total authority’, according to the then County Drama Advisor, Gerard Gould.

Salvation Army preacher, as she enters their bar.

As Gerard noted, ‘The actress playing Lillian has the most challenging task in interpreting Kurt Weill’s “feisty and wonderful songs”, notably Surabaya Jonny, perhaps the most powerful and moving of all his vocal pieces. However this was a triumph, in which Zoe Willis showed not only an amazing vocal but also a considerable emotional range.’

There were other very good actors in the cast who came together to form two vividly characterful teams of gangsters and Salvation Army recruits. They were of all shapes and sizes, of different ages, appearances, performance styles and nationalities, but there was ‘fine ensemble playing’, of which Brecht would surely have approved. Among memorable moments was The Mandalay Song, acted and sung with great glee by gangster Sam Mammy Wurlitzer, gorgeously attired in feminine garb. The other gangsters, Bill, the Reverend and Baby Face, formed a hilarious chorus line on the proscenium stage* behind him.

I have said that performance space has always been important to me. Again I was lucky. I had been teaching drama at New College School and the headmaster gave me permission to use the school hall, for no cost if we didn’t make a profit. As I hadn’t gained permission to access the rights, I wasn’t able to advertise the production, or just minimally to friends of the cast. I didn’t have any official reviewers and the performance was taking place only in a relatively small school hall, so I couldn’t rely on getting large audiences. There was no chance, with tickets at £5 (£3 concessions), that we would make a profit. So I was very grateful that the headmaster had made his initial promise …

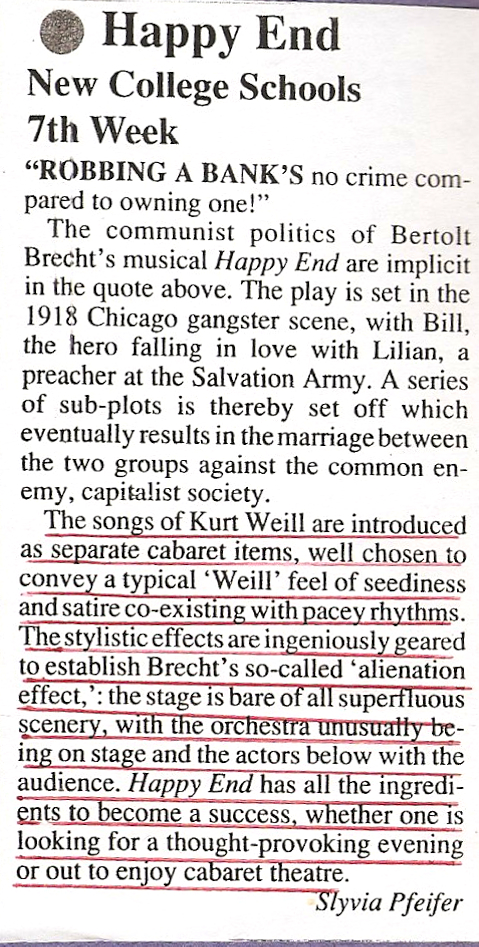

I decided to set the play in traverse, with the student orchestra, (all playing for free under David’s expert direction), actually seated on the stage forming the backdrop. Bill’s Beer Hall, the gangsters’ den, was on the hall floor below the musicians, with a table and a few tatty chairs. The Salvation Army mission was minimally suggested at the other end of the room. As one hardy audience member said, ‘There certainly was nothing cosy about sitting in the New College hall within such close distance of the singers and musicians. Brecht would have approved of the lack of comfort for the audience.’

At this stage in my career, (even after the experience of Jesus Christ Superstar, when the cast gave a ‘donation’ to the musical group), I hadn’t got into the habit of paying musicians for their undoubted contribution to shows. My naïve philosophy was that they had enjoyed the same opportunity as the actors to learn and perform a great theatrical piece, like Bernstein’s West Side Story. The actors didn’t expect payment so why should the musicians? I thought that the experience gained from playing a fantastic score must surely be enough in itself, so it didn’t occur to me that I should pay them!

I had learned my lesson by the time of The Wall, however, and from then on, becoming aware of costs, I tended to employ just one instrumentalist whenever possible: just a pianist for The Threepenny Opera, for example, or a flautist for The Tempest. And that didn’t break the bank!

So, as Brecht would have also appreciated, the performance area was, in Gerard’s words, ‘bare of all superfluous scenery, but care had been taken to provide vivid, characterful makeup and appropriate ‘30s costume, which gave a very lively feel to the play.’

As my first Brecht production, it was great fun and I think the playwright would have enjoyed it. I had ‘taken a group of very personable actors of differing abilities and welded them into a fine ensemble and imposed a unity of style.’

Surely just what the author would have wanted!