See the programme notes for a full description of the performance.

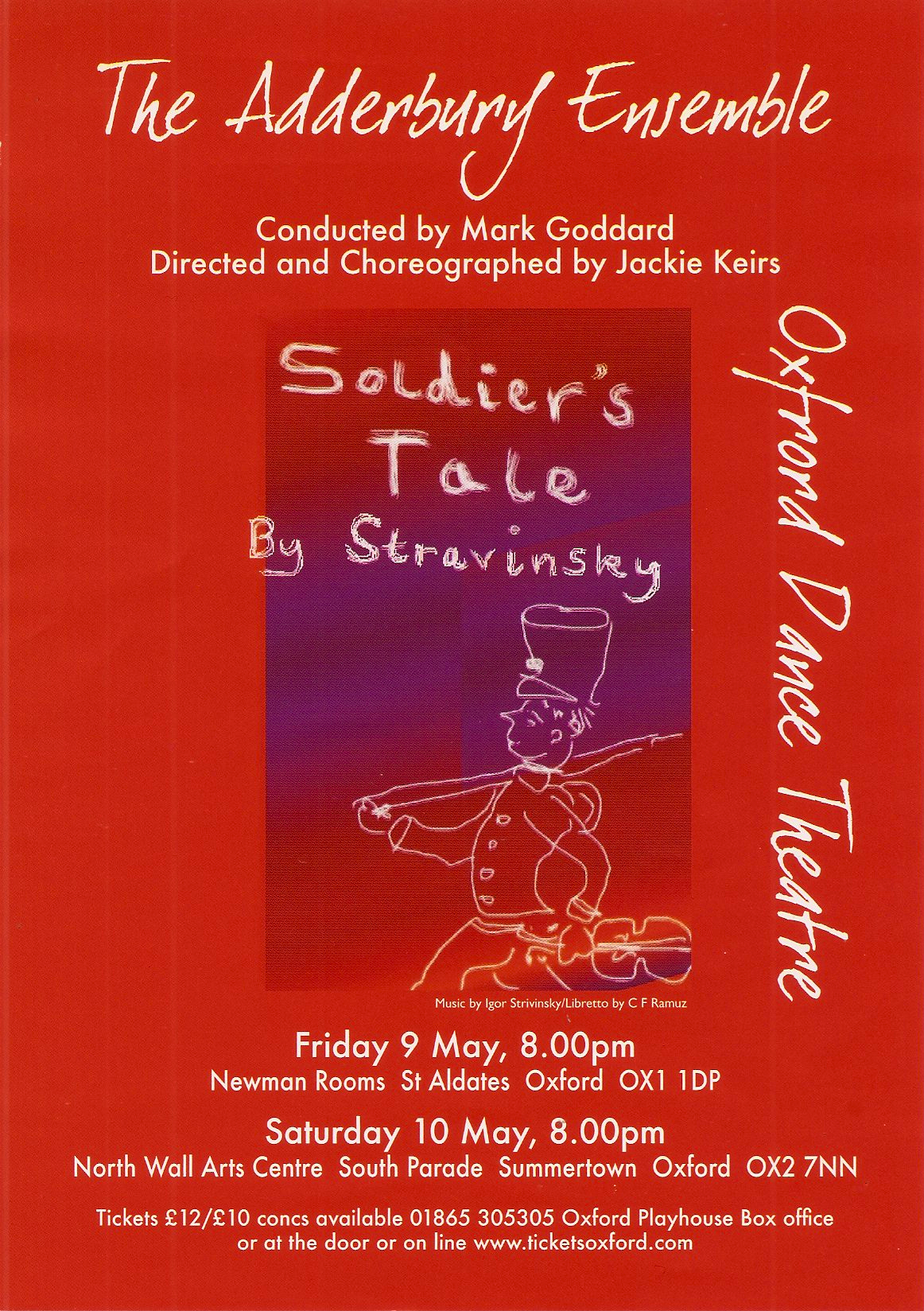

By 2007, I felt that after twenty years of staging one or two plays and musical theatre pieces per year, my career as a director was naturally coming to an end. However, quite out of the blue, Chris Windass, (mentioned in the first chapter as violinist for my 1987 Burton Taylor production of The Soldier’s Tale), approached me. In 2007 he was, as he is still, violinist for the Adderbury Ensemble, highly regarded Oxfordshire chamber orchestra. He also directs Sunday morning Coffee Concerts, an ultimately successful chamber music series, at the Holywell Music Room.

Chris said he had so much enjoyed playing for the original performance of The Soldier’s Tale that we should perform it again. I was surprised and delighted … This very individual piece had played such a fruitful and enjoyable role in my life that I readily agreed. It felt very much ‘part of me’, so it seemed fated that this should be my swansong ... Things had come full circle.

In addition, the story obviously has a universal relevance, its message ever more forceful since the distant, happy-go-lucky ‘60s, when I first choreographed the Devil’s dance for my professor at Birmingham. It struck home with yet more force when, in 2007/8, we began to suffer our own ‘age of austerity’, which continues into the present day.

In January this year, for example, I read the following articles in The Independent: ‘Now, faced as we are with stories of greed and corruption on a global scale, with bosses earning ….% more than the average worker, the prospect of having to live within our means, of finding pleasure in the simple things in life, would seem, for most of us, to draw ever closer.’ Then, ‘It’s good to be reminded that happiness is in the small things. But it may take bigger changes in national life before everyone has the time and freedom to pursue them.’ Or to revert to Voltaire’s Candide in the eighteenth century, ‘Cela est bien dit … mais il faut cultiver notre jardin …’ ie ‘We must cultivate our garden’.

A consistent message for us all.

So The Soldier’s Tale contained all I could wish for in terms of both personal and universal validity. I couldn’t have asked for more.

Mark Goddard, the original conductor for my Burton Taylor production in 1987, was happy to come from Scotland to lead the small chamber orchestra, and Chris of course was keen to play the violin and involve other gifted instrumentalists from the Adderbury Ensemble. As an introduction to The Soldier’s Tale, Mark decided to reprise the original programme. The group played Scott Joplin’s Piano Rags, in his own arrangement, and Ragtime by Stravinsky, both of which contributed vividly to the quality of the evening.

There was a fine young Soldier in Tom Bateman, who had first acted for me in Arturo Ui, in which he played many roles. When I cast him as the Soldier in the 2008 production, he was in a ‘gap year’ between school and gaining a place at LAMDA, since when he has gone on to great things in theatre, film and on television.

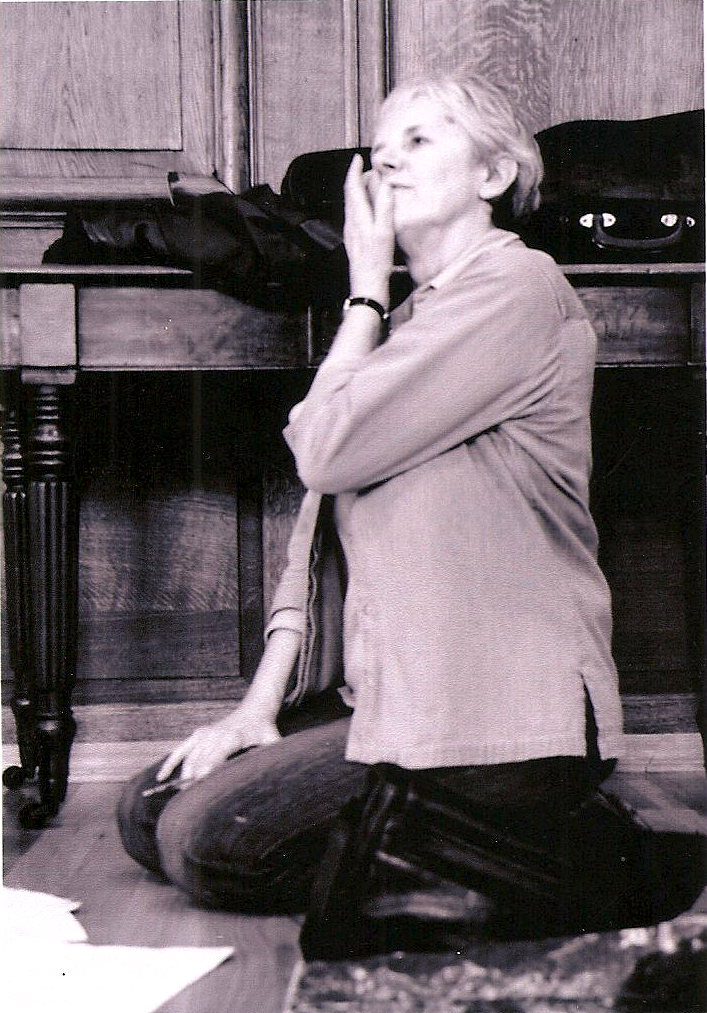

enchanted sleep', Sophie Hollows

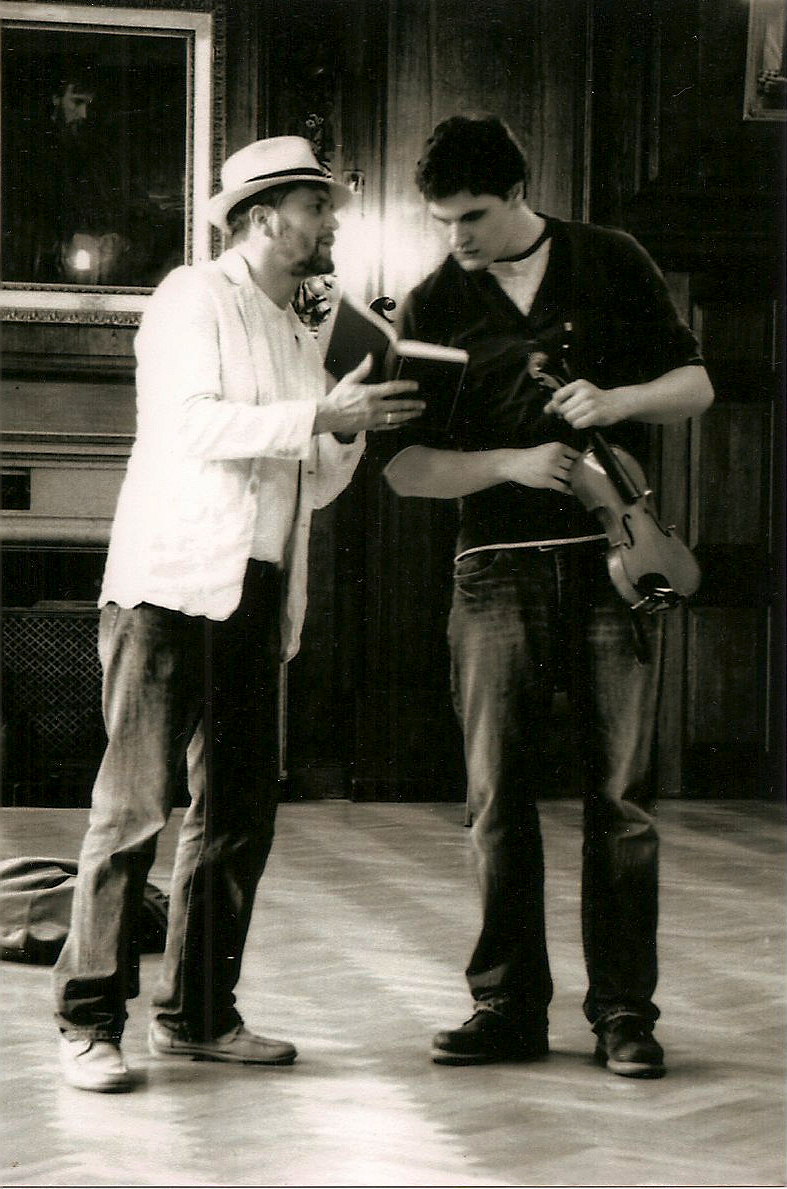

Joseph Adams, who had played the Devil with such panache in my Radley School production of The Soldier’s Tale in 1989, Mephistopheles in Dr Faustus in 2004 and Moriarty in Philip Pullman’s play, Sherlock Holmes and The Lime House Horror, both at the Old Fire Station, was happy to be a Devil again. (Could I be accused of typecasting, I wonder?) According to Joe, he ‘once again donned the garb of a fallen middle-aged angel, the great Satan, Lucifer himself, tempting the Soldier with the power of music and fame and power, while doing some pretty scary stroboscopic freeform dancing in skin-tight leggings and fright-wig, and knocking out cracking tunes on the fiddle.’

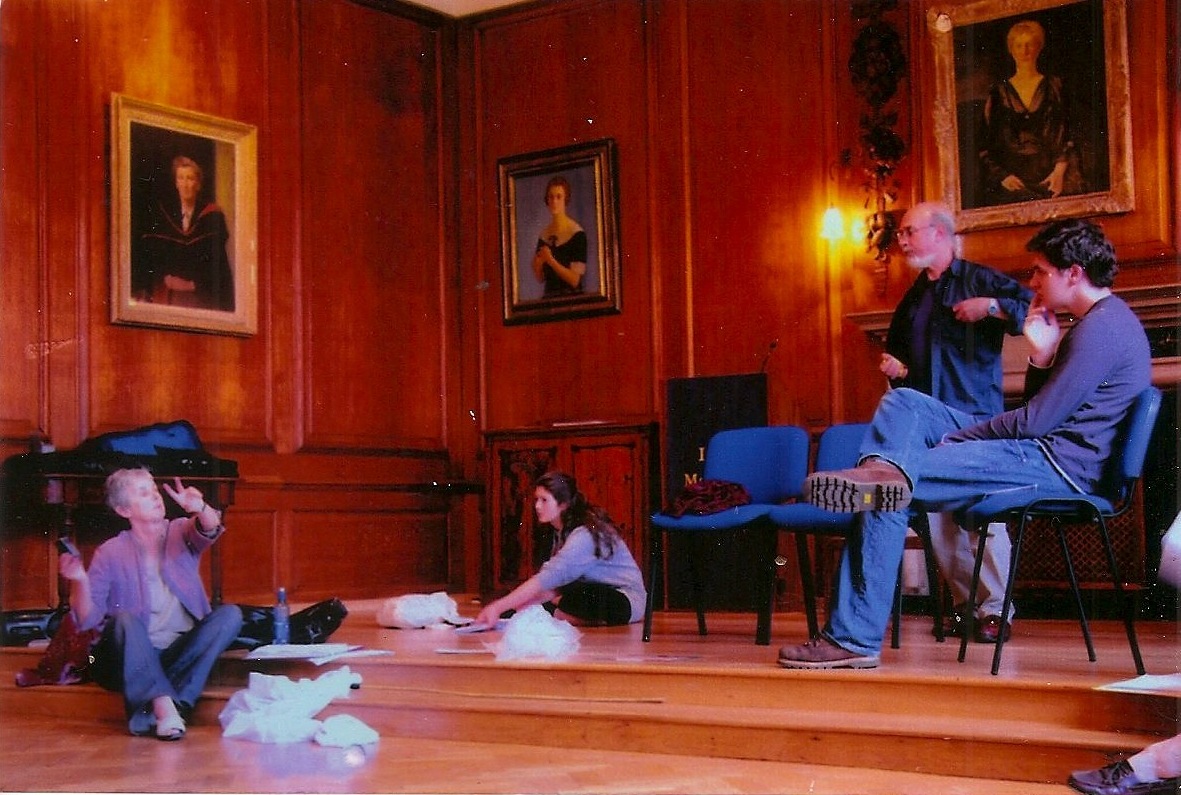

The Devil (Joseph Adams) preparing to play for the Soldier

to dance to his death. All Soldier's Tale pictures are of

rehearsal in Talbot Hall, LMH, where the walls feature

large painted portraits of former tutors.

The Narrator was Jamie Bunting, an actor not previously known to me, so needing more directorial input on my part. He had to ‘talk posh’, not natural for him, but when it came to performance he was utterly convincing.

So a mixture of old and new, in terms of performers and theatre spaces, as ODT had always been, and I was quite content. We rehearsed in Talbot Hall and the Old Library, LMH, both considerably more ‘spruced up’ and highly decorated than when I had known them in the ‘60s, but which inevitably revived fond memories.

Performances were scheduled to take place in the Holywell Music Room, venue for Adderbury Ensemble Sunday concerts, so I choreographed the piece with this space in mind – another opportunity for transformation! As it says in its publicity material, the Holywell Music Room is ‘the oldest purpose built concert hall in Europe. Opened in 1748, its elegance and beauty have played host to many of the world’s greatest musicians and composers.’ Mozart himself is said to have performed there. The room has a classic sense of openness and a gentle calm, with clear walls, candelabra, beautifully proportioned windows and raised wooden seating around an oblong performance area, perfect for the telling of our story.

However, the week before production, Chris came to me with the devastating news that we wouldn’t be allowed to ‘perform’ the piece there after all. He had been informed that movement was not permitted in the Music Room … So very swiftly I had to find two other venues which would be available for performance in the very immediate future – what a challenge!

Fortunately, the Newman Rooms, although not perfect, (being far too large for such a diminutive piece), were available for the Friday evening, so we played our first Soldier’s Tale there. There was no time or money to arrange raised seating etc., so although performance space was more than adequate and there was considerable room for the instrumentalists, there were problems with sight lines for the audience. And, despite many positive comments, there was, for me, little sense of the intimacy inherent in the story.

The Devil persuades the Soldier (Tom Bateman)

to exchange his precious violin for a book which

will bring him 'wealth untold'.

However the North Wall Theatre, which had been open for public use since 2007, was quite unexpectedly available on the Saturday evening. This theatre had been created from what had been St. Edward’s School swimming pool, with a small stage, gently raised seating, ‘boxes’ at either side and a surrounding balcony. It was a delightfully comfortable traditional performance space, with the benefit of modern lighting facilities which, under the supervision of Lighting Director, Jon Smith, made a great contribution to the atmosphere of the story.

In the best of all possible worlds I would have chosen a venue without a raised stage, with the opportunity for more direct contact with the audience, as had always been my practice; this would have been most appropriate for our simple tale. I had been looking forward to the Holywell Music Room, an entirely open performance area with seats raised and more or less ‘in the round’; however the North Wall was a good second best. And it was one of the very few theatre spaces in Oxford that I hadn’t used in 21 years, so an unexpectedly interesting experience for me as my very last show.

We performed a purely spoken version of The Soldier’s Tale as one of the Oxford Coffee Concerts in the Holywell Music Room, where, without action, the story lost a lot of its impact. However we returned with some success to active dramatization of the text at Adderbury church that Sunday evening.

Thinking about it later, there could be said to have been a positive side to all these changes of venue. Perhaps I was actually taking the advice of the original author, Ramuz, when he said in one of his 1917 letters to Stravinsky, ’As there are no longer any theatres, we would be our own theatre. We would provide our own sets, which could be mounted without trouble anywhere …’ I had been providentially provided with the opportunity to perform the piece exactly as had been intended!

And, looking on the bright side, ODT had been true to itself, following its traditional practice: performing remarkable pieces in a series of theatrical venues, with actors from various backgrounds and of varying talents and experience. Changing venue on a daily basis was undoubtedly an unusual challenge for those taking part, but gave them ample opportunity to be imaginative in their response to the demands of different spaces and audiences, which is also what ODT has always been about. We had no trouble staging the piece at any of the venues, since, following Ramuz’ advice, we provided ‘our own sets’; all we needed was a bare stage with a minimum of props, ‘a table, on it a jug of wine and glass, and a chair for the Narrator’ as in 1987. This simplicity and openness in all cases revealed the talents of the actors at their best.

The biggest audience was present at the North Wall, and, despite my doubts, I was glad to have the unheralded opportunity to perform there, witnessing what appeared to be an enjoyable and memorable experience for everyone.

To finish by quoting Joe, the Devil, ‘It was an extraordinary experience, and afterwards I looked back on the process of rehearsal interpretation with undaunted admiration.’

Happy to finish my theatrical career in this way, I have nevertheless, continued to direct evenings of Cabaret once a year at LMH with a blend of actors who have performed for me in the past, and newcomers showing their wares.

So life goes on.