'A play with music' first produced in 1928.

This was another year featuring a musical play by Brecht. Based on John Gay’s 18th century The Beggar’s Opera, the play, with vocal score again composed by Kurt Weill, is a satire on the bourgeois society of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s. According to one critic, ‘with Kurt Weill’s music, this was one of the earliest and most successful attempts to introduce the jazz idiom into theatre.’ The most well-known song is undoubtedly the Ballad of Mac the Knife, Macheath’s caustic, seductive melody ultimately in praise of himself.

Although in the ‘90s I had directed plays and musical theatre in spaces other than the Newman Rooms, all my ‘big shows’ had taken place there. I had used the space in as many ways as I could and now wanted to work in a smaller, more amenable – and cheaper – venue! However, it would have to be quite a bit bigger than the Burton Taylor Theatre, (which I would use only for very special occasions like the plays of Samuel Beckett), or the venues I had used for my two previous Brecht offerings.

the most pitiable of the beggars, Filch (Alistair Tucker).

The Old Fire Station, when it first became an Arts Centre, was basically just two open rooms on the ground floor with smaller rooms above. The ground floor areas were used for classes and dance workshops, which I had given on a regular basis during the ‘70s and ‘80s. Now the largest room had been converted into a theatre which could be used in a variety of ways: traditional end-on, in the round, in traverse and so on. It seated about 200 people, so was just right for me.

I decided to use the stage area in traverse for The Threepenny Opera since the entire play is set in the street – ‘A Fair in Soho’ in fact.

his loud-mouthed wife (Barbara Denton)

and sexy daughter, Polly (Fred Garner).

Robert Bristow (Peachum) commented on the use of space, ‘the uniqueness of the production was in the way the venue was used. The audience were seated, but completely in traverse, so they flanked the action throughout, creating an immersive experience for all, which was also exciting to work within.’ Robert admits that he did find the blocking uncomfortable in the early stages of rehearsal, ‘but as I persevered with the moves – and once we performed them in the traverse stage setting – they somehow made sense. This was part of the way the production followed Brecht’s epic theatre and Verfremdungseffekt concepts.’

The Threepenny Opera was created by Brecht to attack capitalism generally, pointing to the evils of greed and the unfairness of society, a further example of ‘didactic’ theatre. But it is certainly not without ‘spass’, (or ‘fun’) which permeates the text throughout.

The characters are criminals as a form of self-defence, holding their own, profiteering, in a society in which crime is a capitalist enterprise. Macheath, the wily Casanova of this dangerous world, and Peachum, ‘The Beggar’s Friend’, who supplies thieves with their disguises as beggars, have all the bourgeois virtues. Macheath is a business man who does not want his business disrupted, while Peachum sees poverty as a way of making money. The satire is reinforced when, at the end of the play, Macheath is given a royal pardon, together with a handsome pension!

Weill’s music is, as always, superb, and David played the piano as accompaniment, which was just what we needed. (I can’t remember whether we had formal permission for this or not, but, as with Happy End, I couldn’t afford a full orchestra, and neither was there room for one in the traverse setting.) David was described by critic Paul Morris, as ‘creating a cracking pace when needed, supporting the singers through the extraordinary complexities of Weill’s melodic lines and improvising with wit during the scene changes.’

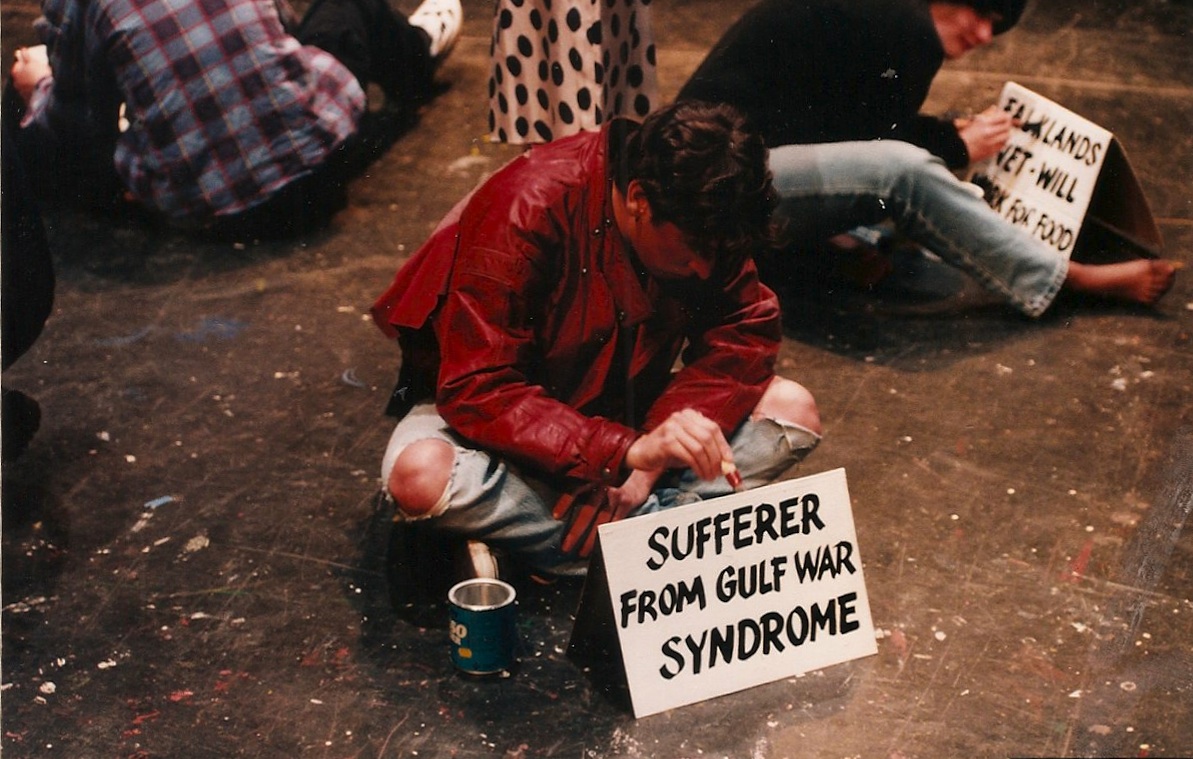

The Threepenny Opera is perennially relevant, so it seemed obvious that I should bring it right up to date. The beggars on the street (a feature of life in the 1930s, the 1990s and a very visible presence now) carried banners saying ‘Sufferer from Gulf War Syndrome’, while signs over the street announced pithily, ‘There is no such thing as Society’, ‘The first concern of government is care of the poor’ and so on. I was certainly doing my best to comply with one of Brecht’s theories: displaying signs ‘to project relevant political messages’!

There was virtually no set, but the few necessary props were well made and well used, as Brecht would have wanted. A stark representation of the jail, which would eventually house Macheath, was visually dramatic and easily transportable, as was the low board table (constructed on stage each night as part of the performance) at which the gangsters wolfed their supper. There was also a balcony, always useful(!), to represent the bedroom where the nubile Polly and Macheath, magnificent in Chinese silk dressing gown, expressed their love for each other. Beneath this was a screen, another visual contribution which Brecht would have appreciated, to reflect the comings and goings of all the characters as they lived their lives in the street, ‘the beggars begging, the thieves thieving, the whores whoring’ etc.

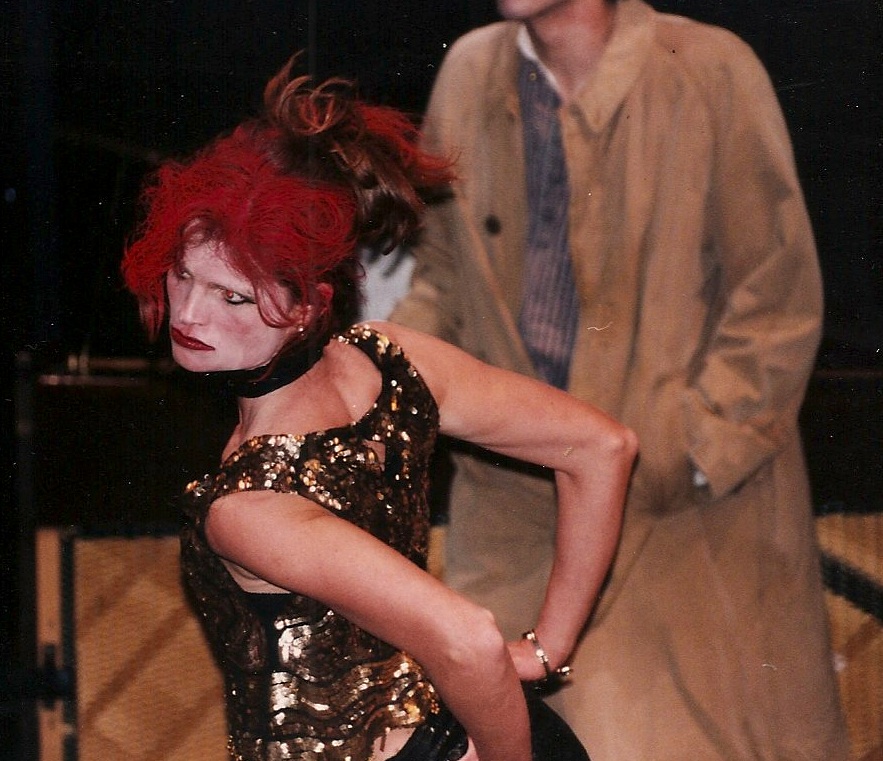

The traverse was colourfully lit, with a series of lights operated by the cast in full view of the audience. Lights were exposed on stands of different heights, making the most of the actors’ movement, and there were vibrant, attractive costumes. These, with clear bright make-up and wigs, gave style and vitality to the characters as they used the stage ‘jumping from attitude to attitude’ as one critic put it.

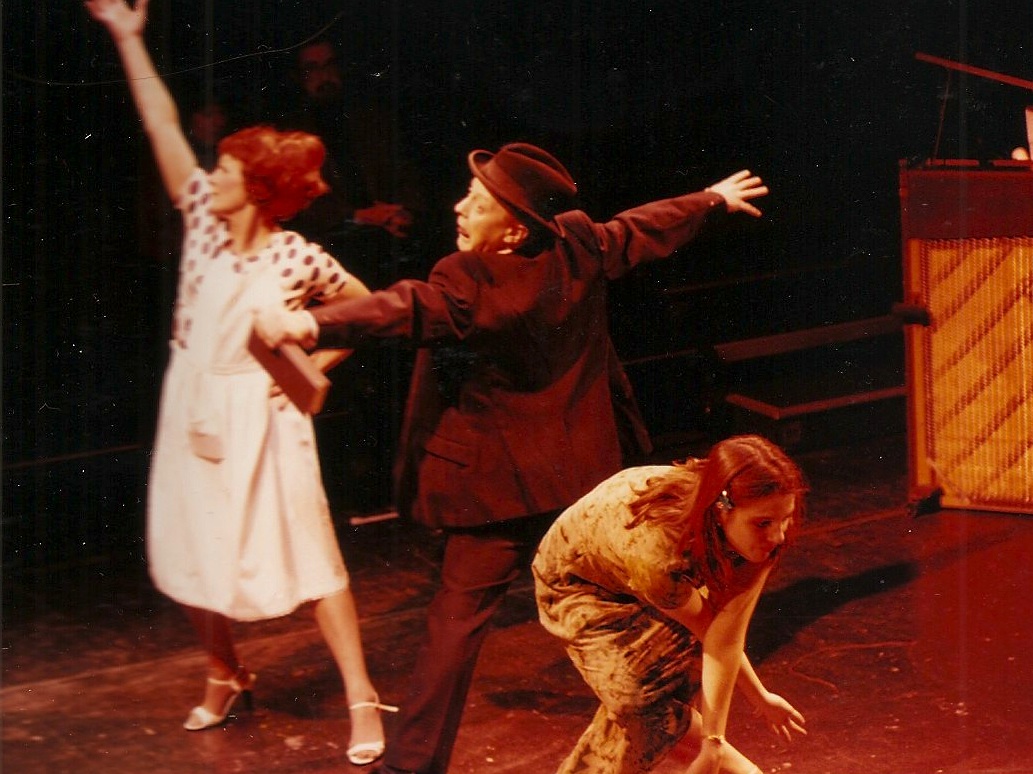

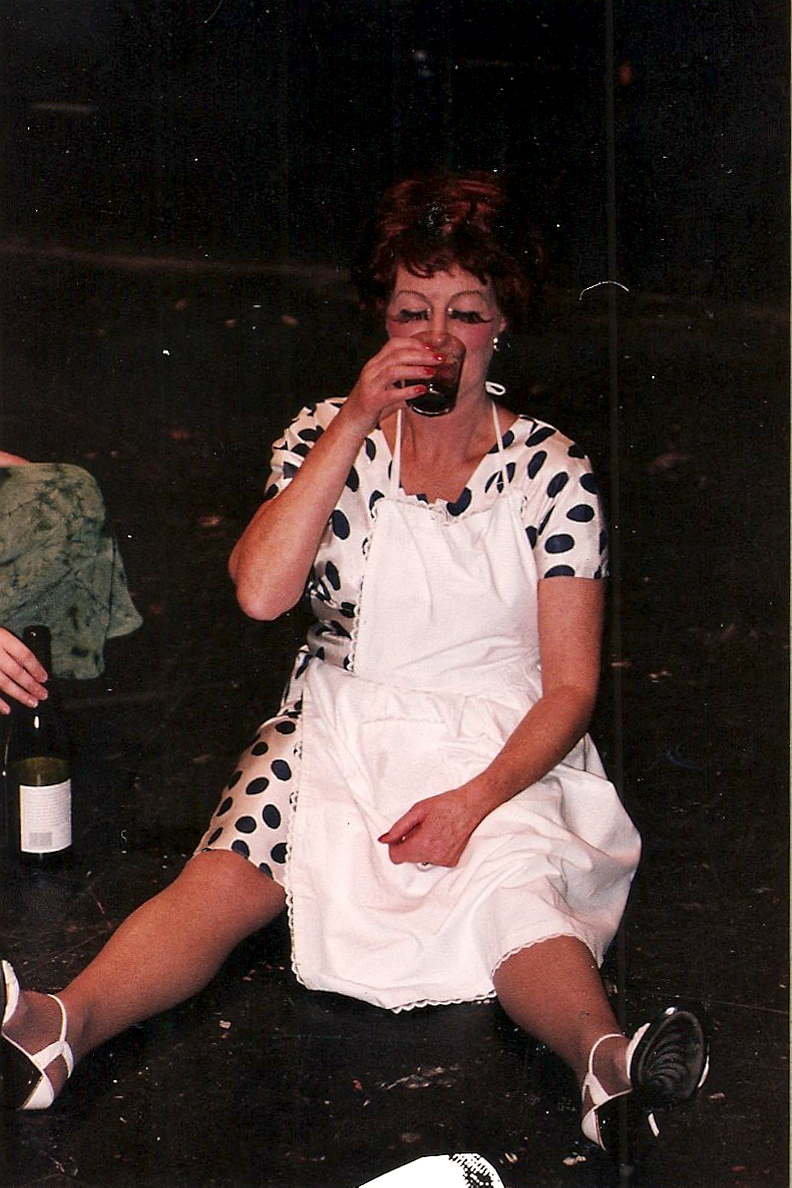

The Threepenny Opera is certainly an ensemble piece and all actors played their parts with style: Robert Bristow ranting as Peachum, Barbara Denton ‘hilariously dotty’ as his wife, Fred Gardener (a girl!) as an innocent but manipulative Polly, Sophie Lucas a scheming, pregnant Lucy, and Marion Baker, the whore mistress, whose ‘stiff caricatural walk conveyed exquisitely the two-dimensionality of Brecht’s rogues.’ Alex Scott Fairley was the charismatic anti-hero, Macheath, whose ‘mercurial performance’ according to critic, Paul Morris, ‘convinced us that so many characters being charmed by him was not quite so uncanny after all. His teasing, cajoling charm worked magic as he interacted with the audience.’ Then there was Chris Walters as the bent cop, Tiger Browne… and more. Altogether a fine array!

Having said that, it was not an easy production for me to direct: there were many problems. At the beginning of the rehearsal period, there was unfortunately a suicide attempt among the cast. ‘Fred’, at first cast as Lucy, now became Polly. So then I had to find another pregnant Lucy, but I was lucky to come across Sophie Lucas, who, bubbly and vivacious, was just right. The actress who was to play Mrs. Peachum dropped out and I had to find someone else at short notice. However, again, I was lucky to come across Barbara Denton, who ‘made a hilarious entry in her role as wardrobe mistress, looking for clothes for different types of beggars and kept the audience enthralled until the end.’ Finally Macheath was offered a big part in another play late in our rehearsal process, but fortunately we managed to avoid clashes, thank goodness.

Just an example of the problems that beset Am Dram!