My first contact with West Side Story came via an informal invite from a fellow University Ballet Club member, summer term 1965, to a matinee performance at what was then the Regal cinema, Cowley Road. So this was the film version of the musical, conceived, directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins, score by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, surely three of the most talented artists of the twentieth century. And, according to critic, Hollis Blake, ‘Never before had Hollywood gone to such lengths to preserve an original work, in the transfer from stage to screen.’

Mesmerising! Unforgettable! I was totally transported, and coming out into a sunlit Cowley road, quite dumbstruck. I had never seen anything like it. As I say in my own minimal programme note for ODT’s 1988 production, ‘an almost perfect fusion of music, lyric, song and dance, it is at heart a choreographic work, first directed by Jerome Robbins, who structured every scene with the precision and discipline of a ballet master’.

There was to be a big gap between being a student aficionado and renewing acquaintance with the musical, which came when I directed a pure dance version with students at Lord Williams’s School (Lord Bill’s) in the 1970s. As I say in my biographical notes, the sixth form boys had been doing their own thing dance-wise with some success when it was a single sex grammar school, but when it became a mixed comprehensive in 1970 a CSE Dance course was established and dance threatened to become the preserve of girls. Until one boy, Ben Forster – I remember him well! - asked if boys could join in the sixth form General Studies Dance group along with the girls. He had seen his school rugby playing heroes relishing the dance experience and wanted some of the excitement!

West Side Story was a clear choice for the students to perform, with its distinct highly dramatic feel and obvious roles for boys and girls. However, at that moment in my career, having been a dancer with an Educational Dance group, the British Dance Drama Theatre (BDDT) for just one year, and a school teacher of dance for two, it did not occur to me to try to stage the whole musical. Unsurprisingly, there wasn’t the talent around; it was quite the wrong time and place.

However it did appeal to me to present a pure dance version of the musical, using Bernstein’s Suite of Symphonic Dances from West Side Story as inspiration. One of my fellow BDDT dancers, Norman Walters, who had performed in the original London production, came to choreograph for us. Our dance version was an immediate success, featuring in school performances at Lord Bill’s and elsewhere. Undoubtedly the most memorable of these was when I used it as part of our 1975 programme at the Round House Theatre; we received a standing ovation from an eager audience of nearly two thousand!

Becoming freelance in 1980, I had by 1988 choreographed many productions: plays, classical and modern, musicals and dance pieces, performed in theatres and school halls ranging from Eton, Radley College and St. Edward’s to local state schools, Cheney and Wheatley Park. I had also just begun to direct, with my production of The Soldier’s Tale in 1987. This had given me a rich feel for text, cast and perhaps above all for the importance of the space used and its contribution to atmosphere. I felt I had credentials to draw on!

However perhaps an even more profound contribution to my feeling for the importance of space had already been made by my own experience as a dancer with BDDT, touring small theatres, colleges and schools throughout the UK. Always a bare stage, sometimes raised, but more often with dancers on the same level as the audience, or with audience members on raised seating facing or surrounding the performers. There was a total lack of set, with lighting, costume and only essential props to convey atmosphere and concentrate focus on performers.

So when it came to directing dance at Lord Bill’s, it was quite natural for me to use the floor of the hall for performance. The audience would be seated on the stage and on two sides, rather than the dancers on stage with the audience looking up at them, as would, in the ‘60s, have been more usual. This seemed much to the headmaster’s initial disappointment, which he expressed in no uncertain terms!

Although I couldn’t articulate it at the time, I felt instinctively that dance was a sculptural form, communicating with the audience in three dimensions. What we call ‘classical ballet’, (eg Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty), was conceived with the proscenium stage in mind, but Louis XIV, who founded the Académie Royale de la Danse in 1661, and was himself a formidable dancer, would perform with his courtiers in the centre of a vast hall applauded by his admiring audience.

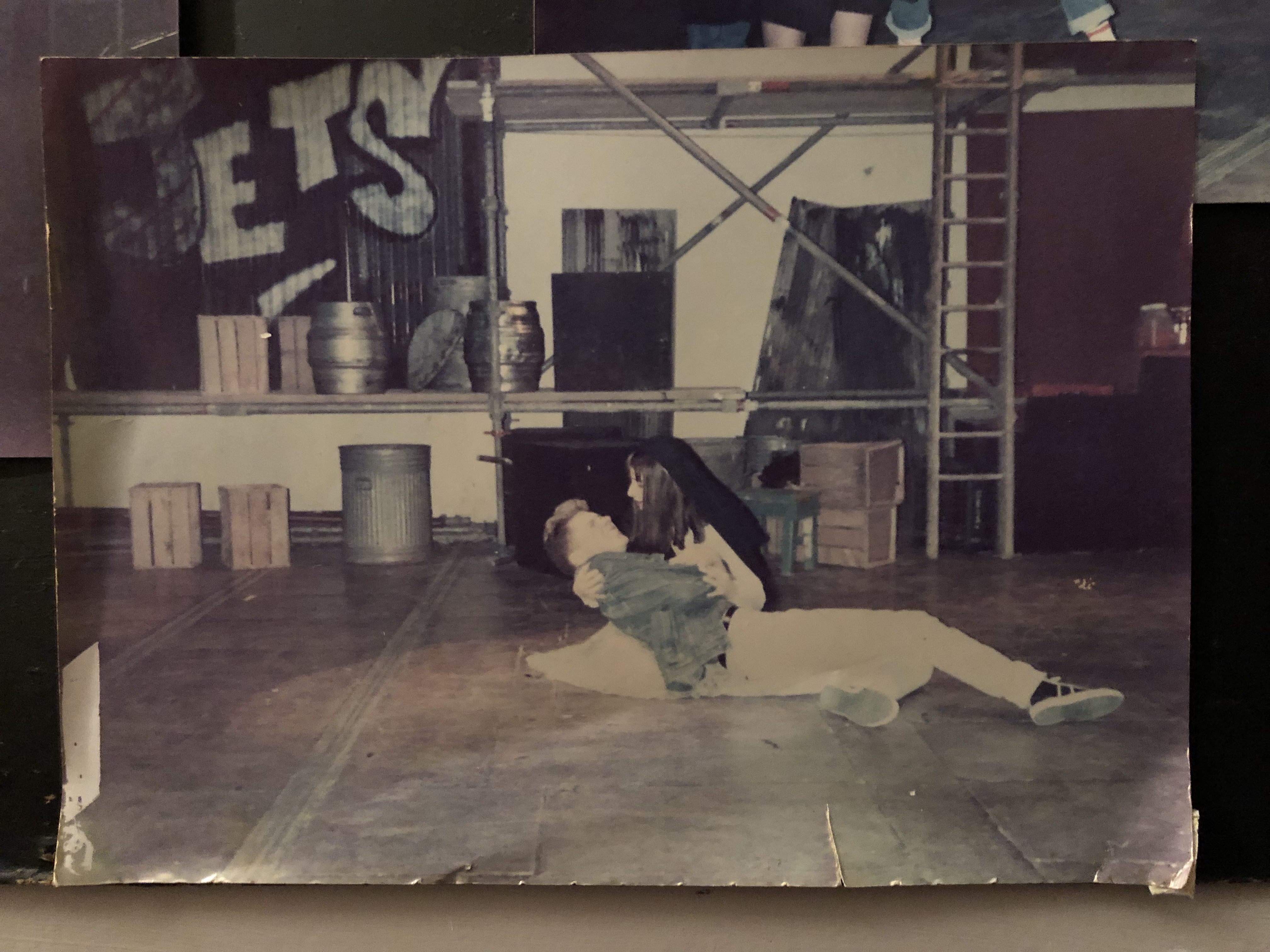

challenges Maria for loving Tony

Modern dance, certainly by the time of Isadora Duncan, for whom the human figure was all important, can be equally valid seen from many points of view. And this physical sharing of space may be especially rewarding when the performers are ‘amateur’, contributing as much in terms of their ‘humanity’ as their technique. Anticipating close connection, the audience will coalesce with the idea of supporting or approving performers, rather than being judgemental. I felt this instinctively when working with the sixth form boys and my preference for this form of staging continued from then on.

Dance or theatre performances, as we are now aware, don’t benefit from being ‘raised on a shelf’, separated from the audience, whose involvement is crucial. ‘We need to work without a theatre’, ‘there are no secrets’, as Peter Brook says. I have myself directed two ‘promenade’ performances, JCSuperstar and The Wall, in which audience members accompanied the action throughout the theatre space. I know how profoundly people can be touched by the openness, truth and vulnerability of the actor in such an intimate situation.

Peter Brook, who supervised the design of the 1940s RSC theatre, Stratford, later expressed regret at his advocacy of a proscenium arch stage as the main performance space. See how many forms of theatrical expression he now commands! From my own small experience, Lord Bill’s students were engaged to perform at the Round House again in 1976, but Peter Brook had covered the floor with sand for a production of The Ik by Colin Higgins and Denis Cannan. So, ironically, the Round House ‘in the round’ became unavailable to us. We had to make do with a rather unfriendly proscenium arch stage at one end, which somewhat diminished the joyful, sharing feel of our 1975 event.

It seems to me that perhaps the most open, versatile and successfully communicative form of staging is that in which actors perform at ground level while the audience is on raised seating erected from the floor upwards. In a clear, uncluttered space, performances can take place with the audience in the round, in the three-quarters, in traverse (the action passing through the spectators), or with the stage ‘end on’, the audience focusing on one area but without the confining frame of the proscenium arch. Contact, visibility and comfort are usually good, and most importantly, the vital, positive feeling of ‘sharing’ is there too.

Flexibility is all, and we are very lucky to live in an age where all these modes of performance are available to us.

Back to West Side Story….

Inspired by the success of The Soldier’s Tale, I felt the need to direct more. West Side Story, which I had known and loved for such a long time, was the obvious choice. I had some familiarity with the Catholic Chaplaincy/Newman Rooms, St Aldate’s, from dancing there as a rose petal in an avant-garde early 1970s ballet, a version of William Blake’s poem, The Sick Rose. The Newman Rooms were an eminently suitable space for West Side Story: large, bare, uncompromising, with a hard stone floor and clinically painted plain walls, absolutely open to theatrical invention. There was also a balcony, as indispensable for West Side Story as for Romeo and Juliet!

A professional designer friend established a scaffolding background along one of the side walls, which, with graffiti and dustbins, served as an all-purpose New York environment, transforming easily into interiors like Anita’s bedroom and Doc’s shop. There was plenty of space for the two gangs to ‘strut their stuff’ alongside the ‘small but excellent’ orchestra.

‘The unsophisticated nature of the Newman Rooms came into its own in this production. With the audience on scaffolding seating in one half of the room and the action before a scaffolding setting in the other, I somehow felt, right from the start, more a participant than a spectator. The corrugated iron sheets scrawled with graffiti, the dustbins and crates, the metal mesh fences and hanging ropes provided a strong basic street setting which was simply but effectively transformed into Doc’s shop, Maria’s room at the Bridal shop with its clothing dummies, as required.’ Theresa Rolf – Daily Information

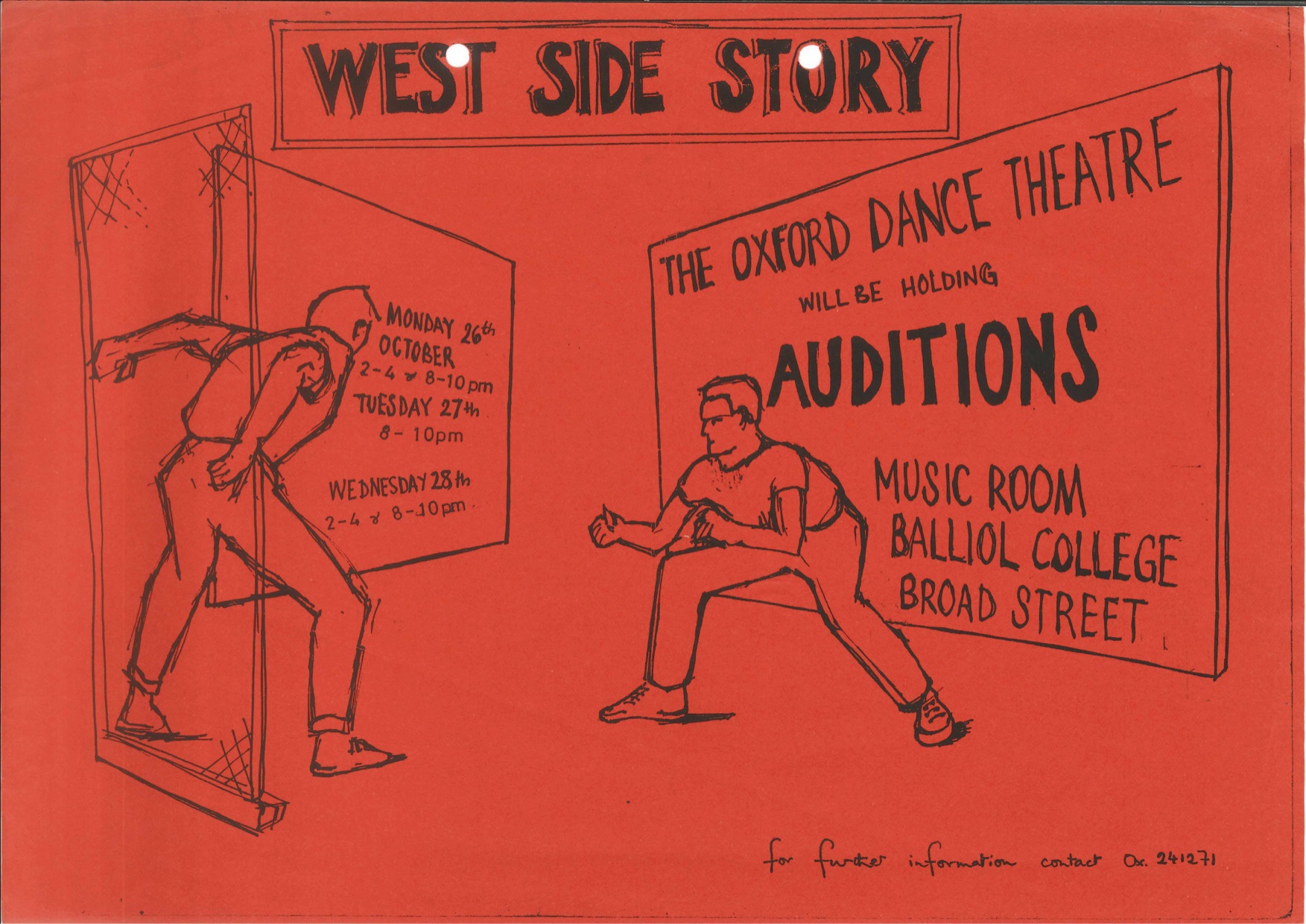

Having chosen the show and the venue, I had a meeting with Mark Goddard, who had musically directed The Soldier’s Tale with such success the year before. This I had produced under my own name, but to put on a show like West Side Story we had to operate as a company, with a company name, to gain rights, pay bills etc. Over a pint in a pub, we fixed on the title Oxford Dance Theatre, if only to bear witness to the role of dance in the show.

So work had begun. There was already a superb Tony in George Kelly, the Devil in The Soldier’s Tale, with whom I had already worked as a dancer/actor, and I knew also of his talent as a singer, a high tenor, just right for Tony. He was the obvious ‘juve’ lead, slim and romantic looking, full of feeling and with naturally fluid movement. Then there were already two characterful gang members who had also acted in The Soldier’s Tale: Adam Coleman, who became Action, and David Allard, A-rab.

Mark and I auditioned for the bulk of the cast – voice, singing, dance and acting – in a miniscule music room in Balliol, which was interesting as actors tried to execute somersaults and other acrobatic moves! I remember David Schneider (writer, actor and comedian) auditioning for Action, laughing as he found the acrobatic movements difficult to execute in such a confined space. He was in his final year at Oxford, so took the cameo role of Glad Hand, leaving Adam to play a totally convincing Action, ‘full of barely controlled anger’ according to the Daily Information review.

The girls were more difficult to cast. We finally chose an American, Betsy Oana, to be Maria. She was a good actress, with a beautiful, pure singing voice, although this was perhaps too fragile when it came to performance. Eventually Emma Kershaw, (now a highly regarded international concert artist), took on the part of Anita; she looked marvellous, singing strongly, with power and emotion, visibly moving audiences every night. Riff, leader of the Jets, was played with energy and charisma by Jonathan Mellor, and Bernardo by George Long, at that time still a student at Didcot School, who looked superbly Puerto Rican, acting, dancing and singing with conviction. Just a few of the cast, but they were all great, and many of them went on to become professional.

There was a more serious occasion involving David Schneider, which is strong in my memory. Mark Goddard had been obliged to resign as M.D. as he had too much professional work, and we recruited a music student from Brooke’s to take his place. Just a few days before opening night, the principals (Tony, Maria, Anita and Action) came to my house late in the evening. I thought they had come with good news of rehearsal, but the reverse – they told me that this replacement was not strong or experienced enough to musically direct a show as demanding as West Side Story. This was very hard for me to swallow and I was in tears. The following morning was spent with Emma (Anita) making phone calls to find out if anyone was willing or available at such short notice to direct such a demanding show.

Fortunately we were surprisingly soon able to contact a conductor, who, although as M.D. busy rehearsing Bernstein’s Candide in Scotland, was happy – for a fee – to fly down every day to conduct for us in the evening. Apparently he was overjoyed to be able to get to know another of Bernstein’s works!

So the principals and I met with the student M.D. then in place to advise him that he was no longer to conduct the show. I invited David to come with me as support. I didn’t know him well but I respected his authority and the obvious reputation he had acquired with other students over three years. And I needed someone to be with me at that stage, having never carried this responsibility before. It was a difficult situation, everyone gathered in a small student room and negative feelings being conveyed – my first encounter with such conflicting artistic temperaments. I remember it well and am very glad that David was there to offer his support. However, under the direction of the newly recruited M.D., the orchestra played superbly and we were very lucky to have them. The musicians played for free, which even then, it seems, was very rare, and certainly wouldn’t happen now!

‘The music is rhythmic with memorable tunes and lyrics. The small orchestra performed it superbly, producing a raunchy sound with strong base for the up-tempo numbers and adapting sensitively to any tempo variations in the slower solo numbers. The singing was excellent both in ensemble and solos.’ Theresa Rolf – Daily information

So when it came to performance things went successfully both for the audience and those taking part.

Interestingly, Emma, who speaks very highly of the show in general, does remember something of this conflict over the M.D. She, as Anita, has the song ‘I like to be in America’, where, as a Puerto Rican immigrant, she sings blithely of ‘the American dream’, while Rosalia, by contrast, has romantic memories of Puerto Rico. As Emma says, ‘Anita has ‘put down’ lines at the end of each of Rosalia’s verses. One night during performance, she gave me a particularly big shove and nearly knocked me over! It certainly added to the drama of the scene!’ The girl playing Rosalia was the former M.D.’s girlfriend so it was perhaps a case of life informing art or vice versa.

Here are just two quotes from actors’ memories of the show: David Allard (A-rab) recalls ‘I particularly recall intensive dance rehearsals, just about mastering a routine, only for Jackie to try a different approach to a step combination or even an entire number, in her bid to constantly improve the show. (I have to say I don’t remember this!) But once we hit the stage and the Newman Rooms with set, lighting, microphones and an orchestra, everything came together and there was an amazing atmosphere. Everyone put their heart and soul into an emotionally-charged production which – from how I felt on stage – seemed expertly to balance high tension and the necessarily lighter moments …’ He then adds a positive personal comment for me, saying that my approach was ‘to build up the production gradually, nurturing and guiding her performers to a point where on the night everyone is fully in the moment. I’ve gone on to train professionally and have appeared in many musicals, but I’ll always remember the excitement of my first!’

Adam Coleman (Action) is also full of praise; he talks about me helping him ‘understand the connection between mind, body and emotions, and how dance is an incredible form of expression’, which, influenced by my study of Rudolf Laban (see autobiographical notes) has been my life’s work. My most overwhelming memory and one that made me realise I wanted to be a professional actor, was the opening night when the character, Tony, was dying and I spontaneously burst into tears – totally absorbed in the story and drama. Twenty years ago I joined Shakespeare’s Globe … I have no doubt that Jackie’s West Side Story and her influence played a massive part in the path that I took.’

But much as I loved the musical, I did find it stressful to direct. This could be, I’m sure, because it was my first big show, because so many rehearsals were going on at once, so many people were involved (a cast of forty!), and I was in charge of all of them, except the musicians, who had their own problems. There were many strong personalities, a real mixture of ‘town and gown’, mostly rehearsing in colleges, including Lady Margaret Hall, my own college, which was a great privilege but at times a cause of friction.

One of the best things about the group being, from the onset, a mixture of ‘town and gown’, was that we were able to rehearse on college premises. So we had access to often beautiful locations, providing a positive ‘feel’ for the actors, enriching their experience and thereby contributing to the quality of the show. Cast members very much enjoyed working in venues normally off limits to non-students.

One instance of the ‘friction’ referred to occurred when we were rehearsing in Talbot Hall, LMH, which we had acquired via Riff, an LMH student. (I couldn’t use my own college connection at that time – I’m not sure why - although I did much more recently for The Soldier’s Tale.) This was an excellent room, just the right size for gang warfare ... The friction was caused by a ‘townie’s’ apparent rudeness to a college bar attendant, allegedly throwing a pint of beer over him, which caused an immediate fracas. I of course had to apologise to the Bursar, but fortunately he didn’t stop us using the hall … phew!

Eventually all came together; the show received rave reviews and we performed before full houses. It’s interesting to reflect on the original New York production, when, ‘after much trepidation on the part of all involved, the opening night was greeted in stunned silence, followed by seventeen curtain calls.’ We didn’t get quite that many, but in the end I felt rewarded for all my hard work, as, I’m sure, did everyone else involved, at every level.

West Side Story has been called ‘one of the greatest pieces of art of the 20th century’ in the recent television programmes commemorating Leonard Bernstein. I consider myself highly privileged to have been able to direct and choreograph such a masterpiece.