My ideas for the production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, are fully set out in the programme notes.

In 2001 I directed A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Old Fire Station, this time using the theatre in traverse, as the subject of the play is a journey, in all senses of that word. Set in the context of ‘transformation’, the traverse setting allowed changes in time and place to happen with remarkable ease, partly through setting and costume, but frequently through the imaginative lighting scheme of Jon Smith, then O.F.S Lighting Designer.

According to Mark Eariss, who played Snug, the Joiner, and one of the fairies, the traverse setting gave great scope to the cast to add ‘their own touches, from being observers of Oberon and Titania to being involved in direct audience interaction’. (I would add that, entirely off his own bat, Snug took advantage of this ‘interaction’ to issue a set of business cards advertising his joinery business to audience members in the front row …)

The version was very 2001 in its approach: Titania and Oberon were ‘celebrities’, actually Madonna and Guy Ritchie, with their own groups of sycophantic hangers-on. Mike Tweddle (Oberon) remembers, ‘When we decided to do the ‘I know a bank where the wild thyme blows’ speech, with me lying on the floor, as in a drug filled stupor, I always imagined the heroin scene from Trainspotting when I did that one.’ Global warming, sex, drugs, it was all there. However the production was, in other ways, a very ‘fairy-tale’ experience.

as Puck, his silhouette projected on drapes

behind him to create another level of reality.

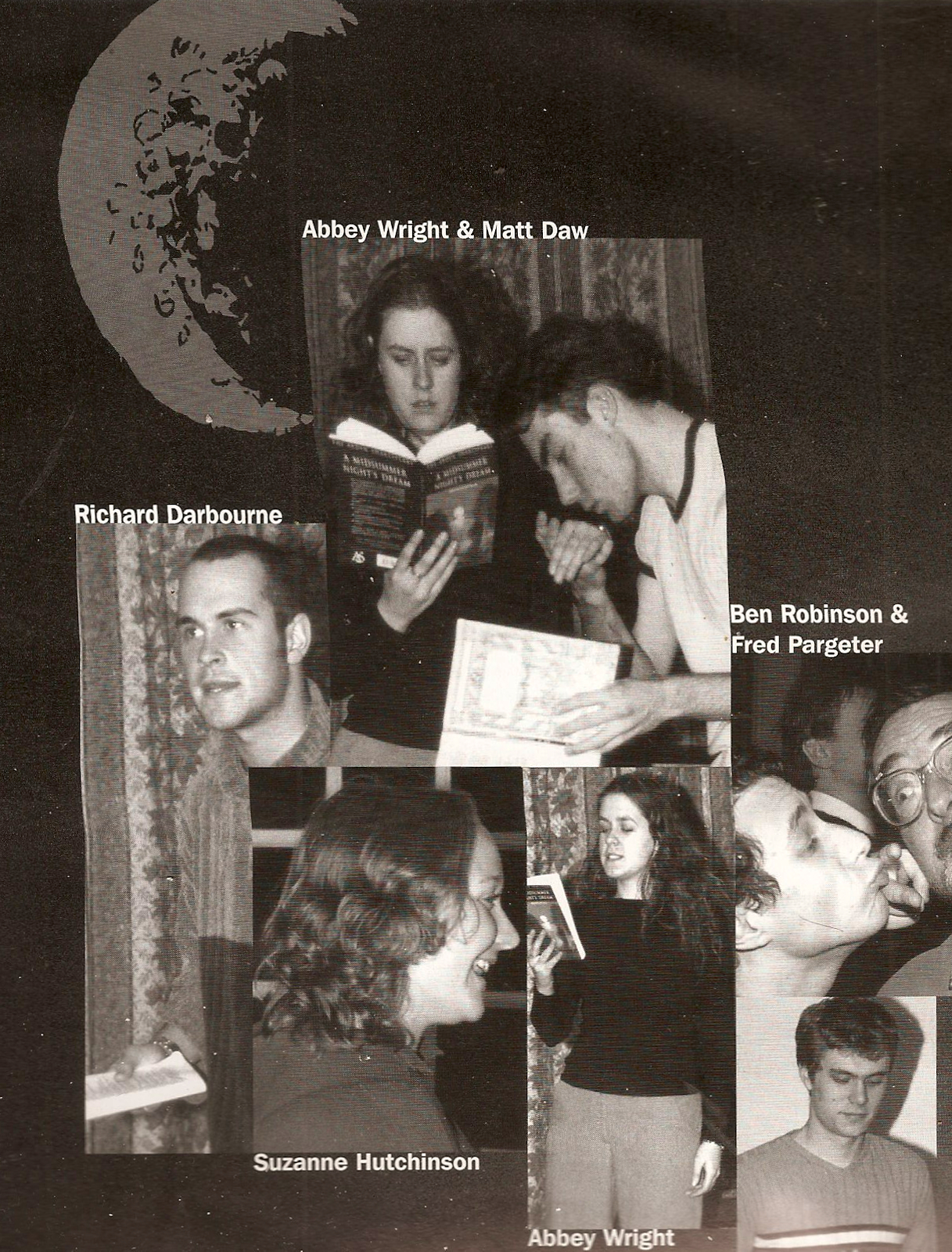

Richard Darbourne, (Lysander) commented, ‘Jackie captured the ethereal and transient nature of the Lovers through a lot of movement and fabulous giant scarves that flowed across the stage and eventually covered the Lovers when they slept. To this day I’ll never know who planted a kiss on my cheek during an interval as I slept. It’s a lovely memory though.’ The ‘fabulous giant scarves’ were ones I had used, many years previously, in various dance contexts at Lord Bill’s; for example to represent the bull fighter’s ‘cloak’ in a dance version of Lorca’s Cruel Garden, or fallopian tubes from dances illustrating Aspects of the Body, which we performed at the Roundhouse. They later floated as symbolic of Pink’s mother’s gown in The Wall.

So there were many agents of transformation, among them sound, light, dance and music, all of which made a vibrant contribution to the ethos of the play.

However, as I say in my programme note, it was actually Simon Garfield who set his seal on the production with his performance of Puck. In my desire to update the play I had been unsure how to characterise Puck, until Simon arrived at audition and revealed his power to ‘change into any shape’. He, as a superb mimic, was able to give Puck ‘a contemporary spin, morphing from David Beckham (dribbling) to Eminem (rapping) to Tony Blair (apologising) – what else!’ to quote audience member, Paul Morris. ‘He fulfilled the theme of ‘transformation’ to perfection!’

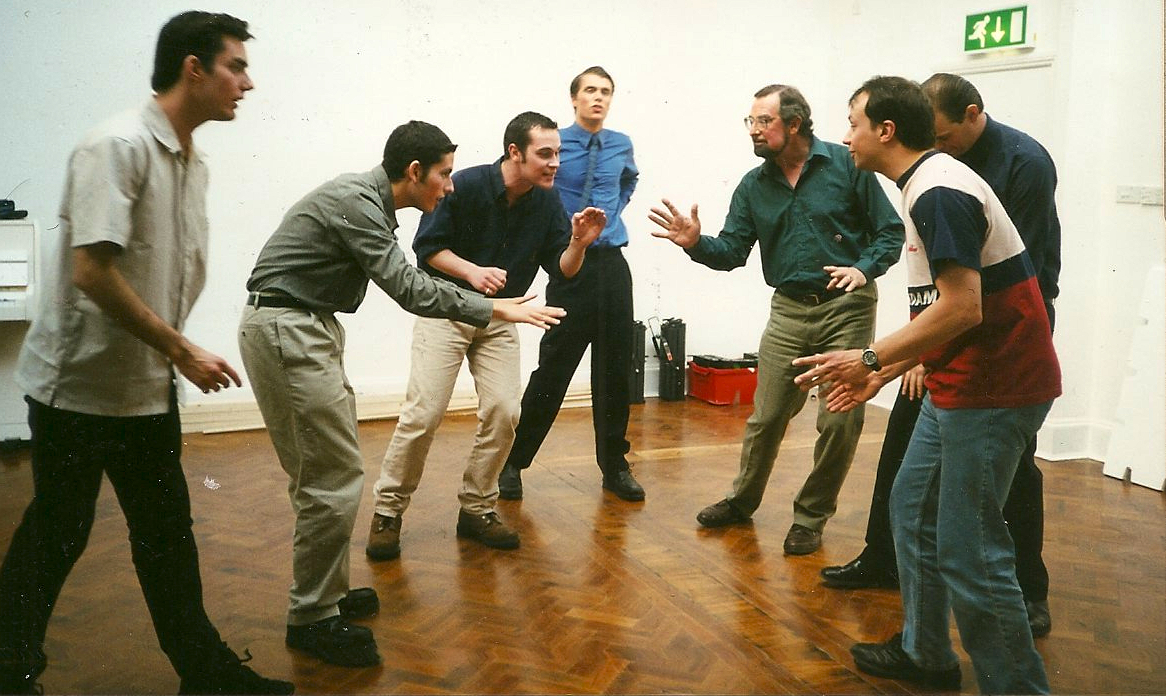

We were lucky to have access to a lovely room for rehearsal in University College, as Ben Robinson, (Flute/a Fairy) was a student there. It was such a pleasure each evening to walk through quiet corridors, past the romantic reclining nude of Percy Bysshe Shelley, to reach our rehearsal room, putting us well in the mood for our rich Shakespeare fantasy ... It was one of the many University rehearsal spaces to which we had privileged access over the years and will always be a delight to remember.

So the Mechanicals became Fairies and vice-versa, and this worked well. The first scene featured these ‘extras’ in Theseus’s court, which changed in the twinkling of an eye to a brown-filled site (no actual set change, just imaginative lighting) with Mechanicals now as working ‘Fairies’ in hard hats and high-viz jackets, carrying torches to fend off evil-doers. Puck was their jovial black jacketed foreman. Mark mentions that ‘many of us had multiple costume changes, for some well into double figures!’

Another, for me, important example of transformation: the relatively minor figure of Flute (Ben Robinson) went through a radical process of change, not just of costume but more importantly in terms of mood, character and heightened speech, as he unwillingly took on the female role of Thisbe in Pyramus and Thisbe, the play eventually chosen by the Duke ‘to ease the anguish of a torturing hour’. I had thought of Flute as a typically bored young recruit to Quince’s community theatre group, constantly on his mobile during rehearsals, but in her final speech, Thisbe reverted to being a male, becoming at the same time a tragic actor whose performance brought the wise-cracking courtiers to silence.

Casting generally worked well and rehearsals were relatively trauma free, although I did have some difficulties with the actress who had played Hermia. I had been happy to cast her fellow Oriel student and roommate as Helena, and the actress auditioning for Hermia, youthful, light and petite, seemed to fit the role perfectly. Living together as students I thought they could ‘do their Stanislavski’ and work up a fine partnership between them … I did have some doubts about the potential Hermia’s voice, which was high, reedy and lacking in warmth, but I put these thoughts to the back of my mind, other priorities taking precedence.

During the rehearsal period, however, things became more difficult. Another student, Porscha Fermanis, had come to a late audition with a group of male friends. She too was small, dark and ‘ineffably beautiful’, (according to Daily Information critic, as Hermione in The Winter’s Tale), with a very expressive voice, just right for Hermia. However, although her male companions all got parts as Mechanicals/Fairies, there was sadly nothing I could offer her as Hermia had already been cast.

I went through a few days of angst, wondering whether I could instead cast Porscha in the role of Hermia, but eventually decided that in Am Dram sacking one actress and employing another ‘is not what is done’. This might well have created personal problems for the girl playing Helena when it came to sharing a room with the presently cast Hermia, who would have been rejected by me. This played a large part in my decision. I knew that the present Hermia was very committed to the role, so I gave up my dreams and did my best to carry on, which was hard work, both for me and her fellow actors! However, I would admit that, although she was not perfect in the first romantic encounters with Lysander, she was a natural in the scratchy, turbulent scenes where the lovers quarrel later in the play.

The blokes who came to audition with Porscha were perfect for Mechanicals. I have already heaped praise on Benjamin Robinson, the 4th year medical student playing Flute; Sandeep Banerjee acted Snout with some glee, although he had to be bullied by the others to remember his lines; Mark Eariss convincingly portrayed a Snug with ‘mental health issues’, and a Spaniard, Mark Amat y Suque, my lodger at the time, was cast as Starveling. He spoke barely any English so sadly found some of his lines cut, but the few he actually uttered, especially in Pyramus and Thisbe, were just right. Alex Nicholls as Quince, the harassed community worker in charge of the group, valiantly kept his players under control.

to look even more beautiful

by her resident hairdresser

and make-up lady

Fred Pargeter (Stephano in The Tempest) played very much in character as Bottom. He did have mood changes throughout rehearsal, much like the character, the most memorable of which was the time when, as lead Mechanical, he walked out of a rehearsal with the bold announcement, ‘You can find yourself another Bottom!’ There was a moment of stunned silence as other cast members watched his dramatic exit; fortunately, however, he rather shame-facedly returned, very much as Bottom himself would have done, so we were able to proceed with the show...

Phew!

Programme Notes